Last updated: April 10, 2025

Article

“This We Shall Remember:” Eisenhower and Victory in Europe

Eisenhower Presidential Library

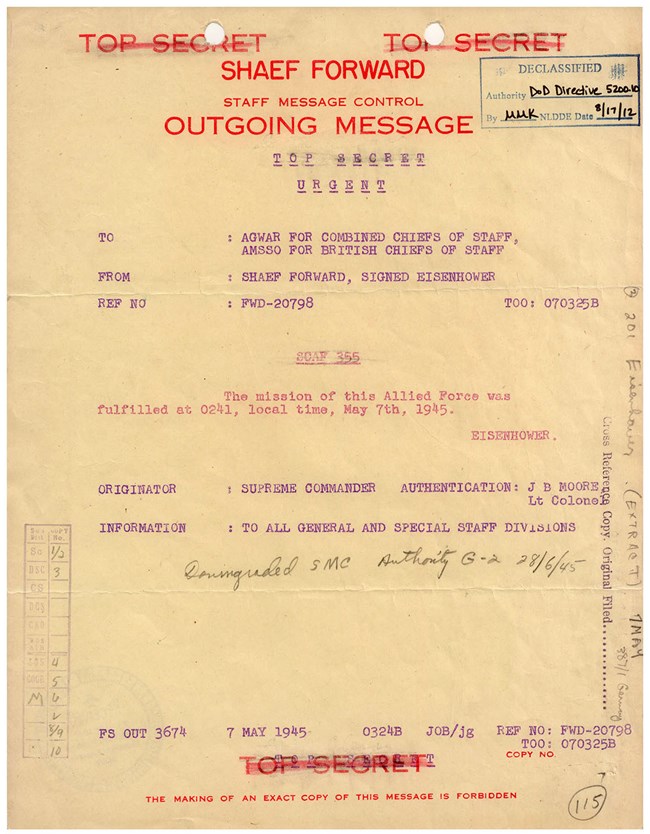

“The mission of this Allied Force was fulfilled at 0241 local time, May 7, 1945.”

With those words, General Dwight David Eisenhower informed the Allied high command that after years of fighting, bloodshed, and destruction, Nazi Germany had surrendered. World War II in Europe was finally over.

While today this moment in time is celebrated—and rightfully so—history reminds us that victory in Europe in World War II was not inevitable. Eisenhower and the Allied Expeditionary Force experienced their share of hardships and moments where their cause—and all that was depending on it—nearly slipped away.

The Allied war effort in World War II was characterized by constant debates over strategy and tensions between commanders. There were setbacks on numerous battlefields, especially early on in North Africa, when Eisenhower and the Allies were learning how to fight and win together. As the Allies closed in on the borders of the Third Reich, casualty tolls grew higher and higher. In the final eleven months from D-Day to VE Day, the perils of weather in Normandy, missteps and setbacks in Holland, surprises in the Ardennes, and the turmoil of war threatened the Allies at every turn.

Eisenhower himself dealt with more than his share of stress on the long, uncertain road to victory. His decades long army career prior to World War II had not been easy. Dozens of moves to various posts around the world, personal struggles for he and Mamie, and worst of all, the death of the couple’s first child, Doud, in 1921, meant that Eisenhower had a track record of heartache and perseverance.

During the war, those past experiences prepared him for what lay ahead. In three years, he only saw his wife, Mamie, twice. He smoked heavily, drank over twenty cups of coffee a day, and dealt with rumors and doubts over his ability to lead. In 1942, his own father and brother died within a few months of each other . With the all-consuming war effort, Ike was not able to attend either funeral. He also missed his son John’s West Point graduation, which took place on D-Day, of all days. Ike dealt with bickering commanders, competing strategic goals, and balanced it all in the face of Nazi tyranny and the might of the German military.

Even in the spring of 1945, in the war’s final weeks, obstacles to victory remained. As the Allies plunged deeper into Germany, concerns grew over German forces splintering and continuing the war beyond the impending fall of Hitler’s government. Floods of refugees and discoveries of concentration camps shocked the world. Eisenhower himself witnessed the Ohrdruf Camp on April 11 and was profoundly changed by what he saw.

Amidst this backdrop, American and Soviet forces closing in on each other caused unease in Moscow and Washington.

Eisenhower knew the alliance between the Soviets and the Western Allies was tenuous. Despite internal pressure for the Americans to take Berlin, Eisenhower opted for the Western Allies to focus their advance elsewhere, ceding the German capital to the Soviets. This decision would have long lasting impacts beyond the end of the war.

Eisenhower was also aware of the feelings held by the Germans regarding the Soviet Red Army. After years of horrific fighting on the Eastern front, many German soldiers and commanders were loath to surrender to the Soviets, fearing repercussions for the scorched earth fighting that characterized the Eastern Front. Many Germans believed they would get a better deal, and better treatment, from Eisenhower and the Western Allies.

When approached about German forces surrendering only to the Western Allies and not the Soviets, Eisenhower was dismissive. Any surrender would be unconditional and would be to all the Allies.

Even in the final days, tensions remained. On May 6, Ike wrote to Mamie, “These are trying times. The enemy’s armed forces are disintegrating, but in the tangled skein of European politics nothing can be done, except with the utmost care and caution… How glad I’ll be when this is all over, when though some of our worst headaches will come after all the shooting is over.”

That same day, on the evening of May 6, Alfred Jodl, the German Army Chief of Staff, went to SHAEF headquarters in Reims (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), seeking once again to surrender only to the Western Allies. Ike refused a separate surrender. He did grant that if the Germans signed a general surrender, the Americans would keep their lines open to German refugees. He also granted a 48-hour wait before its announcement, giving more time for German soldiers to flee toward the Western Allies and avoid Soviet capture. The Germans agreed.

With this back and forth, the last, desperate throes of the Third Reich were a testament to the vicious fighting that had taken place between the Germans and the Soviets. They also put on full display the tensions that would turn American and Soviet allies into foes once they no longer shared a mutual enemy. The final days of World War II became, in essence, the first days of the Cold War. Eisenhower sensed this, though even he had little idea of what dangers still lay ahead.

In this moment, though, as the clock ticked past midnight and May 6 became May 7, the Cold War was still in the future. In those overnight hours, with the Germans in agreement on surrendering, victory in Europe was at hand, at last.

At 2 AM, on May 7, at SHAEF headquarters in Reims, with Eisenhower waiting in an adjacent room, Alfred Jodl signed the German surrender. After signing, he was brought into Eisenhower’s office. The Supreme Allied Commander asked if Jodl accepted the terms. Jodl agreed, bowed, and left. The war in Europe was over.

Upon the signing of the surrender, Eisenhower dictated his brief message to Washington D.C., and then went to bed.

The following day, May 8, 1945, was declared VE Day to celebrate Victory in Europe. Around the world, the news was celebrated by dozens of nations and heralded in dozens of languages. In the United States, millions attended church and wept for those who were lost. Millions more celebrated in the streets in anticipation of those who would soon be coming home. Even then, many millions also greeted the news with firm resolve, knowing that the war against Japan in the Pacific still continued.

On May 8, George C. Marshall, the Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, wrote to Eisenhower, praising his leadership and perseverance through the trials and tribulations of war. “You have completed your mission with the greatest victory in the history of warfare,” Marshall noted. Marshall was uniquely positioned to offer such thoughts, as without him, Eisenhower likely never would have become Supreme Allied Commander. Marshall had been a mentor and role model for Ike, who helped enable his successes while running the war effort from the U.S. That relationship made Marshall’s praise for Ike quite poignant: “Through all of this, since the day of your arrival in England three years ago, you have been selfless in your actions, always sound and tolerant in your judgments and altogether admirable in the courage and wisdom of your military decisions.”

Eisenhower would offer his own thoughts on the meaning of the day as well, issuing a Victory Order of the Day to those under his command. Eleven months after his D-Day Order of the Day, where he told the Allies they were embarking on a “great crusade” to eliminate Nazi tyranny, Eisenhower reminded them of how far they had come:

“The crusade on which we embarked in the early summer of 1944 has reached its glorious conclusion,” Ike began. He praised the Allied Expeditionary Force “for valiant performance of duty” on the road to victory.

Ike acknowledged the challenges they had encountered and overcome along the way, writing: “On the road to victory you have endured every discomfort and privation and have surmounted every obstacle ingenuity and desperation could throw in your path. You did not pause until our front was firmly joined up with the great Red Army coming from the East, and other Allied Forces, coming from the South. Full victory in Europe has been attained.”

As his message closed, Eisenhower focused on honoring those who had been lost. With Europe covered in cemeteries, filled with the dead of many nations, Eisenhower drew inspiration from their sacrifices, which he hoped would guide the post-war world:

“The route you have traveled through hundreds of miles is marked by the graves of former comrades. From them has been exacted the ultimate sacrifice; blood of many nations – American, British, Canadian, French, Polish and others – has helped to gain the victory. Each of the fallen died as a member of the team to which you belong, bound together by a common love of liberty and a refusal to submit to enslavement. No monument of stone, no memorial of whatever magnitude could so well express our respect and veneration for their sacrifice as would perpetuation of the spirit of comradeship in which they died. As we celebrate Victory in Europe let us remind ourselves that our common problems of the immediate and distant future can best be solved in the same conceptions of cooperation and devotion to the cause of human freedom as have made this Expeditionary Force such a mighty engine of righteous destruction."

“Let us have no part in the profitless quarrels in which other men will inevitably engage as to what country, what service, won the European War. Every man, every woman, of every nation here represented, has served according to his or her ability, and the efforts of each have contributed to the outcome. This we shall remember – and in doing so we shall be revering such honored grave and be sending comfort to the loved ones of comrades who could not live to see this day.”

May 1945 was a moment of supreme triumph for Eisenhower. Yet in this moment of victory, he chose not to venerate himself. Instead, he looked back at the long, turbulent road to success. From the headstones of the fallen, Eisenhower saw lessons of cooperation, togetherness, and unity. He was keenly aware of the growing tensions between the American and the Soviets that would dominate the post-war world.

Through all he had seen and experienced, Eisenhower chose to remember the hardships and the victories together. His life experiences taught him that ultimate triumph can only emerge from adversity, as it had for the men and women of the Allied Expeditionary Force. Through the suffering of war, Eisenhower remained hopeful victory meant a better world was possible.

In this light, Eisenhower sought to give meaning to those lost by seeking to prevent such bloodshed again in the future. Much as Lincoln had articulated at Gettysburg in 1863, in 1945, Eisenhower asked that the sacrifices of World War II not be in vain. In so doing, and by so remembering, Eisenhower hoped their example would guide the world toward peace.