Last updated: April 23, 2025

Article

"A Citadel of Women's Independence"

The National Woman’s Party, Congress, and the Fight to Preserve the Belmont House

By Dr. Caitlyn Jones, Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellow

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

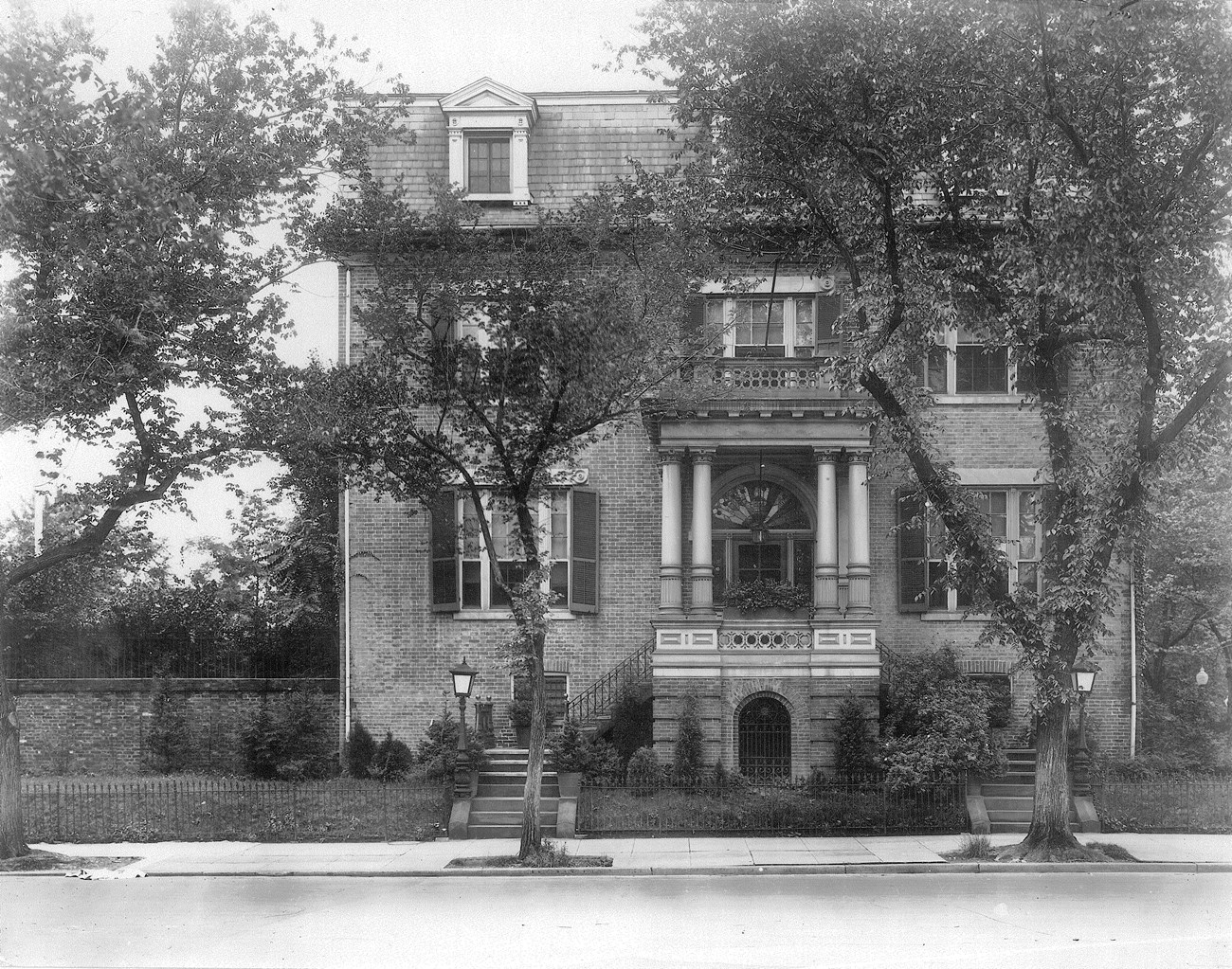

In January 1931, the National Woman's Party (NWP) opened the doors to its fifth and final headquarters. The Georgian-style home in Capitol Hill had stood since the early 1800s. Once the NWP came along, it became the Alva Belmont House. Speakers at the dedication ceremony dubbed the house a “laboratory of feminism” and a “citadel of woman’s independence.”1

Alva Belmont herself, the wealthy socialite who purchased the property, had high hopes for the future of the home. “May it stand for years and years to come," the NWP president predicted, "telling of the work that the women of the United States have accomplished; the example we have given foreign nations; and our determination that they shall be – as ourselves – free citizens, recognized as the equals of men.”2

The issue of how long the Belmont House would stand immediately came into question from its next-door neighbor, the US Congress. Twenty-four days after the dedication ceremony, the House Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds held a hearing on a bill to demolish the NWP headquarters. They wanted to make way for a new Bureau of Accounts building.3 The bill failed, but it sparked a decades-long battle between Congress and the NWP over control of the property.

Today's visitors know the Belmont House as the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument. The NWP knew it as a symbol of their proximity to political power and their perseverance as an organization. Upon its founding in 1913, the organization made its home in four different headquarters in only sixteen years. They lost previous buildings to eviction or seizure from the federal government; the Belmont House, their last headquarters, meant a place of their own. So, they spent the next forty years fighting Congress to keep it.

As fierce protectors of the Belmont House, the NWP carried on a tradition of women as historic preservationists. Much of its energy – and most of its resources – went toward repairing and maintaining the home. And its historic significance changed over the years as the modern women’s movement grew. By the time the National Park Service became the owner of the site in 2016, the NWP had transformed the Belmont House from a home of "great men" into a shrine for their own feminist heroines.

“May it stand for years and years to come, telling of the work that the women of the United States have accomplished; the example we have given foreign nations; and our determination that they shall be – as ourselves – free citizens, recognized as the equals of men.”

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

On the President’s Doorstep:

Early NWP Headquarters

The NWP started in 1913 with grand ideas in humble spaces. Alice Paul and Lucy Burns founded the organization first as a branch of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the nation’s leading suffrage group at the time. The duo raised funds to rent a small basement office at 1420 F Street NW for $60 a month – almost $2,000 in today’s money.4 From here, they planned a massive suffrage procession in 1913 that became known as the first civil rights march in Washington, DC.5

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

Silent Sentinels

The NWP launched their famed picket campaign from this headquarters. Women emerged from Madison Place each day and crossed the street to stand guard in front of the White House. They held up banners urging President Woodrow Wilson to support suffrage and faced arrest by local police. Sometimes, angry crowds gathered outside of headquarters itself. One picketer, Ernestine Kara Kettler, recalled someone shooting through an open window at the women inside.8

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

The landlord of 21 Madison Place did not like the negative publicity the NWP brought to his property. So, in early 1918, he evicted them.9 The NWP moved across Lafayette Square and rented a house at 14 Jackson Place. Within these walls, members pushed for ratification of a constitutional amendment recognizing women’s right to vote. When the amendment passed on August 26, 1920, Alice Paul unfurled a celebratory banner on the balcony of Jackson Place.

Purple and gold stars dotted the fabric, representing each of the thirty-six states that ratified.

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

New Mission, New Building:

The NWP Moves to Capitol Hill

After the Nineteenth Amendment passed, the NWP turned its sights toward a new goal: legal equality for women. Knowing that they would need help from Congress, leaders set their sights on a new home base: Capitol Hill. In 1921, they purchased three rowhouses at 21 First Street NW. Washingtonians called the complex the “Old Brick Capitol” because it was the temporary home of Congress after the British burned the former Capitol in 1814. The NWP used this headquarters to lobby for equal employment and citizenship laws as well as the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA).

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

National Woman's Party, Library of Congress

A Female World:

The NWP in the Belmont House

The loss of their headquarters did not mean the end of the NWP’s residence in Capitol Hill. In 1929, NWP president Alva Belmont purchased a new house roughly 1,000 feet away from the Old Brick Capitol. The Belmont House brought renewed energy to the NWP as they continued their ERA campaign and took up international advocacy. At the 1931 dedication ceremony, Sen. Thaddeus Caraway (D-AK) declared, “The last shot to strike down injustice would be fired from the Alva Belmont House.”11

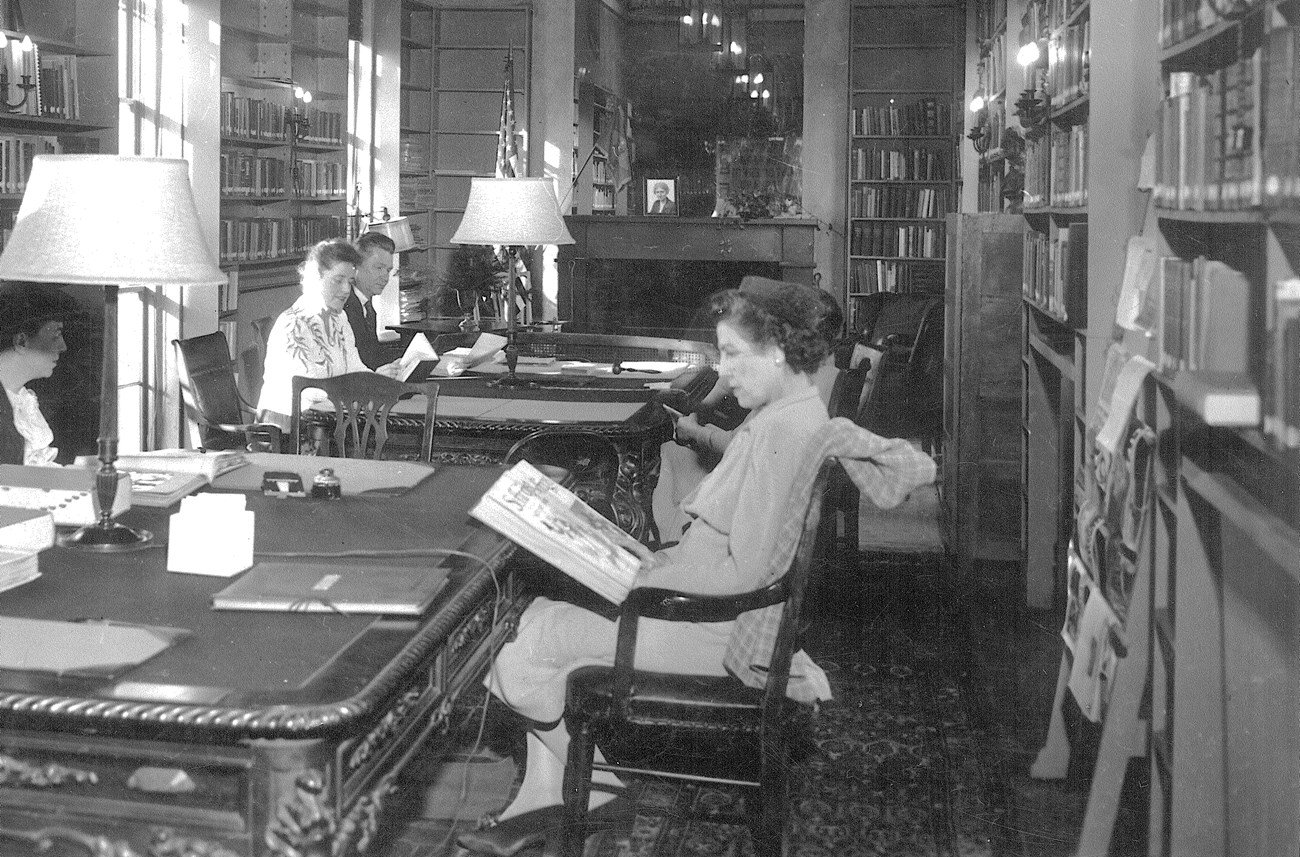

Despite these encouraging remarks, the NWP struggled to gain widespread legislative support for its cause. So, the Belmont House offered a feminist refuge for women working in the male-dominated, and often hostile, world of Congress. Several members lived in the home and the group often rented rooms to scholars, lobbyists, and international visitors. Historian Leila Rupp wrote, “The environment of the house was so woman centered that one member wondered in 1945 if being married would prevent one's acceptance there.”12

National Woman's Party

National Woman's Party

“The more beautiful we make this property, the more chance we have of keeping it.”

Saving the Belmont:

Preservation and the NWP

The NWP needed these allies as the federal government expanded dramatically over the course of the twentieth century. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Senate searched for more office space for its ballooning Congressional staffs. They decided the nearby Square 725 – which included the Belmont House – would be a prime location for a new building and held hearings on its potential purchase.15

National Woman's Party

At first, NWP leaders rallied against this by trying to improve their headquarters. As one member put it in 1932, “The more beautiful we make this property, the more chance we have of keeping it.”16 They built a brick patio and terrace for events in the garden and transformed a carriage house into a feminist library.17 But upkeep of the house was expensive, and the NWP struggled to keep up with repairs. They shifted course and began promoting the historic value of the Belmont, partnering with historic preservation groups and other women’s organizations to save the house from the Senate.

National Woman's Party

The instinct of NWP members to preserve their home was not new. Women had led many of the nation’s major historic house preservation efforts for more than a century. Founded in 1853, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association transformed George Washington’s dilapidated home in Virginia into a shrine for American patriotism on the eve of the Civil War.18 Years later during the Jim Crow era, the National Association of Colored Women raised thousands of dollars to refurbish Frederick Douglass’s Cedar Hill home in Washington, DC.19 Many of these women felt it was their civic duty to preserve the homes of prominent American men, especially during times of political and social unrest.

In Congressional hearings and publicity campaigns, NWP members considered themselves patriots as they emphasized the history of the male residents of the home. They spoke of Robert Sewall, the patriarch of a prominent Maryland family who built the house. They glorified American soldiers who fired on the British during the War of 1812. And they commemorated Albert Gallatin, the Secretary of the Treasury during the Jefferson and Madison administrations.20

By putting the spotlight on men instead of themselves, the NWP made a strategic choice to spur preservation efforts. In the 1950s and early 1960s, national preservation programs focused mostly on sites with military, political, or architectural significance – areas where women’s contributions were often excluded.21 Congress responded to the appeal for male history by granting tax exemptions to the NWP and excluding it from expansion plans. Yet, the organization struggled to get landmark protections. The NWP applied for landmark status in the early 1960s under the “architecture” designation by dating the house back to the 1600s.22 A National Park Service advisory committee denied the application in 1965. One member said it possessed “no nationally significant architectural distinction” and “lost whatever original architectural integrity it had” in later renovations.23

National Woman's Party

Civil rights movements caused shifts in preservation practices by the 1970s. Historians began to recognize important places for women and people of color. The NWP seized the moment. They placed the house on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and the Secretary of Interior designated it as a National Historic Landmark two years later. This time, members and preservationists argued that the NWP is what made the Belmont worth saving. “Its significance does not lie in its architecture,” National Park Service historian Carol Ann Poh wrote in the nomination form, “but in its historical associations, especially its association with the organization whose militancy was indispensable to passage of the 19th amendment.”24

Even with this landmark status, the NWP still hesitated to fully center their own history. The new name of the building tells us as much. The NWP registered the property as the Sewall-Belmont House, foregrounding the original male owner instead of their own feminist leader.

“Its significance does not lie in its architecture but in its historical associations, especially its association with the organization whose militancy was indispensable to passage of the 19th amendment."

N. Adams/National Park Service

Conclusion: Owning Women’s History

The preservation of Sewall-Belmont changed the trajectory of the NWP. Its landmark status finally protected it from demolition as the new Hart Senate Building sprang up around it. Just as important, it made the NWP eligible for government grants to help with costly repairs. Over time, the organization shifted its focus from lobbying to preservation. In 1997, it became an educational non-profit that fully embraced women’s history. Members ran a public museum dedicated to the NWP, opened their library up to researchers, and hosted events honoring women in politics. To many, Sewall-Belmont represented the Mount Vernon for women.25

The NWP dissolved in 2020 and the Sewall-Belmont, now the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument, is under the care of the National Park Service. There are many stories that still need to be told at the Belmont House, but there is no doubt that it is a site dedicated wholly to women’s history. Its place on Capitol Hill – standing defiantly alongside the Senate – reminds us of the determination of the women who lived there and their fight to be part of history.

Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship

This article was made possible through generous support from the Mellon Foundation in partnership with the National Park Foundation and American Conservation Experience. Learn more about the Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellowship.

References

1 Ruby A. Black, “Alva Belmont House Is Dedicated,” Equal Rights, January 10, 1931.2 Black, “Alva Belmont House is Dedicated.”

3 “Alva Belmont House Threatened,” Equal Rights, January 31, 1931.

4 Alice Paul and Amelia Fry, “Conversations with Alice Paul: Woman Suffrage and the Equal Rights Amendment,” 1976, Suffragist Oral Histories, The Bancroft Library Oral History Center (Berkeley, CA) https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217358?ln=en&v=pdf (hereafter referred to as Alice Paul Oral History).

5 Rebecca Boggs Roberts, “The Great Suffrage Parade of 1913,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/the-great-suffrage-parade-of-1913.htm.

6 U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, “Tayloe House,” May 2010, https://cafc.uscourts.gov/wp-content/uploads/Library/Tayloe.pdf.

7 Mabel Vernon and Amelia Fry, “Mabel Vernon: Speaker For Suffrage and Petitioner For Peace,” 1976, Suffragist Oral Histories, The Bancroft Library Oral History Center (Berkeley, CA) https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217361?ln=en&v=pdf.

8 Ernestine Kettler and Sherna Gluck, “The Suffragists: From Tea-Parties to Prison,” 1975, Suffragist Oral Histories, The Bancroft Library Oral History Center (Berkeley, CA) https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/217310?ln=en&v=pdf.

9 Alice Paul Oral History.

10 Edgar Williams, “The Old Capitol starts a Row: Building of National Woman’s Party in Washington Limelight,” Baltimore Sun, August 12, 1928, M9; Quinn Evans, “Historic Resource Study: Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument,” US Department of Interior, January 2021, 2-12, https://www.npshistory.com/publications/bepa/hrs.pdf (hereafter referred to as BEPA Historic Resource Study).

11 “Celebration Begun as Woman’s Party Dedicates Offices,” Washington Post, January 5, 1931, 14.

12 Leila Rupp, “The Women's Community in the National Woman's Party, 1945 to the 1960s,” Signs 10, no. 4 (Summer 1985), 727.

13 Rupp, “The Women’s Community,” 728.

14 “Minutes of the Council of the National Woman’s Party, September 24, 1932,” Box V79, Folder 2, National Woman’s Party Records, Library of Congress (Washington, DC); “The Alva Belmont House in Summer,” Equal Rights, August 5, 1933.

15 “Senate Unit Votes $4.5 million to Buy 1 1/2 Blocks Near ‘Hill’ Area,” The Washington Post and Times Herald, Feb. 9, 1956; “Extension of Capitol Grounds,” Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds of the Senate Committee on Public Works, January 19, 1960; “Authorizing for Extension of New Senate Office Building Site,” S. Rpt 90-735, Committee on Public Works, 90th Congress, 1st Session (Nov. 8, 1967).

16 “Minutes of the Council of the National Woman’s Party, January 17, 1932,” Box V79, Folder 2, National Woman’s Party Records.

17 Quinn Evans, “Cultural Landscape Report: Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument,” US Department of Interior, January 2021, 2-34 through 2-44, https://www.npshistory.com/publications/bepa/clr.pdf (hereafter referred to as BEPA Cultural Landscape Report).

18 Patricia West, Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books, 1999).

19 “Preservation,” Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, National Park Service, last updated December 14, 2022, https://www.nps.gov/frdo/learn/historyculture/preservation.htm.

20 “Extension of Capitol Grounds,” Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Buildings and Grounds of the Senate Committee on Public Works, January 19, 1960, 11-46.

21 Sarah Pawlicki, “Women’s Histories and Representation in the National Historic Landmarks Program, 1960-2024,” US Department of Interior, 5-6.

22 Later architectural studies have noted this to be untrue. A 2001 study of the early structures of the Belmont House dates it to 1799. BEPA Cultural Landscape Report, 2-15.

23 Letter from Richard Howland to S. Dillon Ripley, May 29, 1974, “Washington, DC NHL Sewall-Belmont House NHL Landmark,” National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, RG 79: Records of the National Park Service, National Archives and Records Administration, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/117691869.

24 Carol Ann Poh, “National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form – Alva Belmont House,” US Department of the Interior, August 23, 1973, https://npshistory.com/publications/bepa/nr-alva-belmont-house.pdf.

25 Script for Alva Belmont Specialty Tour, Box V221, Folder 4, National Woman’s Party Records; BEPA Historic Resource Study, 3-57 through 3-77.