Last updated: February 20, 2025

Article

(H)our History Lesson: Papago Park Prisoner-of-War Camp in Tempe, Arizona WWII Heritage City

Courtesy of Steve Hoza.

About this Lesson

This lesson is part of a series about the World War II home front in Tempe, Arizona, American World War II Heritage City. The lesson contains readings and photos to contribute to learners’ understandings about the Papago Park Prisoner-of-War (POW) Camp.

The length of the lesson can be shortened, or readings selected based on objectives and interests. Each reading shares distinct information surrounding the camp but together show a more complete picture of the complexities and challenges at the camp. The first reading set includes oral history excerpts that share prisoner and guard experiences from the camp. The second reading shares details on the capture of prisoners who escaped Papago Camp in the largest escape from a POW camp in the United States during the war. The final reading, an opinion piece, could also be considered an extension reading. The reading can be used to analyze a set of beliefs and some of the home front controversies surrounding the POW camps in the US, including Papago Park.

Objectives:

- Describe the conditions and social dynamics of the Papago Park prisoner-of-war (POW) camp using primary sources.

- Explain benefits and obstacles of the POW camp to the local Tempe community, including the implications of the largest POW camp escape during the war.

- Synthesize local, historical perspectives on the complexities and ethical questions surrounding POW camps on the U.S. home front.

Materials for Students:

- Readings 1, 2, and 3

- Recommended: Map of Arizona, with Tempe marked

- Images-- All images from this lesson are available in the Tempe, AZ Gallery:

Getting Started: Essential Question

Getting Started: Essential Question

How did the presence of the Papago Park prisoner-of-war camp affect the city of Tempe?

Read to Connect

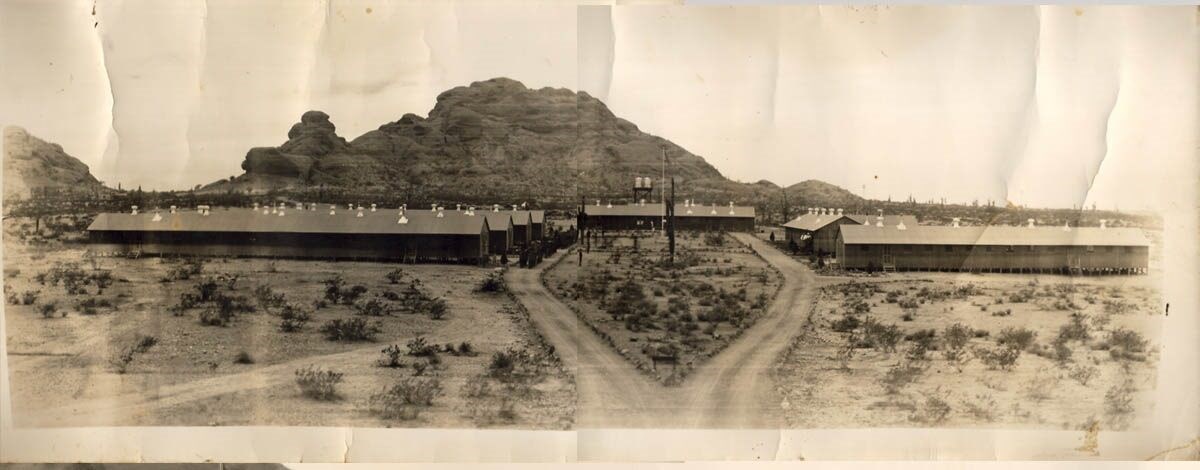

Background: The Papago Park Camp was located on the ancestral lands of the Papago Tribes. The federal government used the land for a Civilian Conservation Corps encampment then a location for US Army combat training. In October 1943 the center was converted into a prisoner-of-war (POW) facility, first for Italians, then Germans. The first group of Germans arrived in January 1944.

The camp had multiple facilities, including barracks, recreational areas, and workstations where prisoners were employed, mainly in local agriculture and camp facilities. US service members were stationed there to guard and oversee the prisoners and camp security. Despite this, the camp became well-known for a mass escape in December 1944. 25 POWs dug a tunnel out of the camp, though all were eventually recaptured.

Voices of the Papago Park Camp

The following interview excerpts are courtesy of Steve Hoza, from the book “PW: First-person accounts of German Prisoners of War in Arizona” (1995). Hoza spent nearly four years interviewing and corresponding with former prisoners, camp guards, and civilians in Arizona. The book provides a comprehensive look at life in Arizona prison camps, and highlights stories from the Papago Park Camp, including the escape.

Teacher Tip: Consider dividing narratives among students. In a jigsaw format, each student or group can read a different narrative, then come together to share key insights, helping the whole class build a comprehensive understanding of the varied experiences within the camp. There are not specific questions for each narrative, as students will be expected in general to note and share details about their pieces, but there are questions to synthesize and summarize across the excerpts.

Bill Pederson, US Guard

The site of the camp was extremely barren. There was no grass. There were no lawns. In fact, any little piece of growth that would come up was pulled to keep it looking neat, but it was an extremely barren place. We were really impressed with the possibility that they were going to do some terrible things. I don’t know how long it was after they were in the camp that all these concerns seemed to go by the wayside and they were soon working in the kitchens doing KP (kitchen patrol) and things like that. . . .

The enlisted men [prisoners] all received good food and medical care. We had a large hospital there. Their clothing was GI clothing with the stencil ‘PW’ on the back. The German officers were treated exceptionally well. If you were a company-grade officer, they would put two of you in a little two-bedroom cabin. A field-grade officer such as Captain Wattenberg had a cabin to himself and had a German prisoner as an errand boy. . . .

I never saw any particular problems with the prisoners except for the fact that they were so cocky and sure that they were going to win the war and everything we said to them was propaganda and they didn’t believe us.

Hans Lammersdorf, German Navy

“ . . . On the train from Houston to Camp Hearne [Texas] to Papago Park, they had separated the Whites from the Blacks. We prisoners of war were in the White compartments. We were not with the Blacks. They had their own compartments. In the railroad station in Houston we saw the separated facilities. The restrooms, Black and White. We looked at it and thought ‘By golly, what’s going on here?’

The Blacks had their place. We talked to them in North Africa. We saw them here and there. We felt they were completely separated. I saw the division in Texas in Camp Hearne. They were mainly Blacks. We could see that they were not accepted. We felt close to the Blacks. Closer than you did because we were at the mercy of the military. We had not many rights, neither did the Blacks. In a way we felt closer to them and those [POWs] that could speak a little English would talk to them. I would, too. We knew their position was no better than ours. We could tell that. But again, we were amused that Americans could criticize us for the racial prejudice when they had some of their own. . . .”

Karl-Hans Friederich, German Navy

In the beginning we did not have to work, but later we were given work assignments. I did many different kinds of work. At first we shoveled canals that irrigated cotton fields. After that we removed the weeds from these fields. For a few weeks we were assigned to an onion harvest. In January or February 1945, a detachment of prisoners to which I belonged was brought to the outcamp Eleven Mile Corner. The camp lay directly by a canal where the water for the cotton fields would come. We lived in 6-man tents. Only the kitchen and washroom were solid buildings. On the other side of the canal there was nothing but desert. We were brought to work in a big cotton wagon and you couldn’t sit down. Each day we had to pick 80 pounds of cotton. Whoever did not produce had to work on Sunday.

For a short time I worked on a small farm. The farmer and his wife were both teachers. I remember that he always used the expression ‘chicken and ice cream.’ As our work for him came to a close, he asked us all what we would like to eat on our last day. At the same time we all said ‘chicken and ice cream.’ That is exactly what we had for lunch. That family was very friendly to us.

Josef Mohr, German, submarine U-513

We were awakened at six in the morning. After roll call and a good breakfast, the work teams organized at the main gate. Then the trucks and other vehicles arrived and took us to our work sites. In the evening, when we were led back into the camp, we were frisked to make sure we weren’t bringing anything illegal into the camp.

There was another roll call before dinner. We were then free for the evening. The most popular activities were soccer and handball. In Compound Four we built a sports field in a corner near a guard tower. We played soccer here every evening. The guards in the towers enjoyed watching our games. If someone was injured we would signal to the guard who would telephone for an ambulance. We had a good rapport with the guards.

The prisoners liked to build flower gardens in front of the huts. We would take wood from the spars in the hut ceilings to make benches or canopy shades. We also used the wood to make ship models and other beautiful things. . . .In the summer, it was too hot to sleep in the huts so we slept outside.

Other POWs had pens for little animals like dogs, chickens, duck and pigeons. This was quite a common, everyday sight in the camp. The American administration in the camp was very tolerant of the things we did. They were mostly concerned with keeping order.

Ray Radeke, Guard:

One thing I could never understand was the civilian curiosity and fascination with the POWs. Civilians, mostly young women, would hang around and walk around places where the POWs were working such as the laundry in Phoenix. The civilians would not go away and leave it alone and we would have to call the local police who would chase them off. The civilians would go up in the high places around Gunsite Pass near the camp and watch the Germans with field glasses. They would tease the POWs by sunbathing, etc., which was just asking for trouble. I could never understand the fascination with these ‘supermen’ who were killing Americans by the thousands in Europe and on the oceans!

Heinrich Palmer, German Navy

Once the Americans distributed a large questionnaire throughout the camp filled with a lot of questions. Maybe they thought that there would be a fool among us that would answer all the questions correctly. They wanted to know, for example, where our boat had been stationed in Germany or France, when did we leave port and which ships did we attack or sink. They wanted to know what our stations and functions on board ship had been and a lot more. We answered the questionnaire. An entire U-boat crew, for example, under the question about their function on board, wrote ‘cook,’ so that the entire crew were cooks. One man who had been on a ship over Christmas wrote that he had been the Christmas tree decorator.

The food at Papago Park was very good. We received the same food as the US soldiers who guarded us. The food was brought in raw on trucks to the different compounds. In each compound was a kitchen barrack where a fellow POW who was a cook prepared the food. There was, for example, fresh milk that came in bottles. The cook would collect the cream from these bottles and each prisoner on his birthday would have a cream cake baked for him with a few friends along to help him eat it. Cream cakes as a prisoner of war! We sometimes thought we were in Schlarafenland [‘the land of milk and honey’].

Friedrich Riedel, German Army (Located nearby, Camp Florence)

I have many good memories about my captivity. I honestly feel that, despite the barbed wire, I was freer during my imprisonment in America than after my return to civilian life. In America we lived in a democratic society which was a real education.

I have many lasting memories. The great, wide land. The advanced technology. Our fair treatment. The importance of the individual. That was far from the accustomed German government system. The vastly better food. I felt more like a guest than a captive in a distant country.

Teacher Tip: Both Part A and Part B are used to share about the escape of 25 German prisoners. Part A was published in Buffalo, New York, and shows the far reach of the story across the country. The text can also be used to connect to today’s understandings of the displacement of indigenous peoples from their native land and will share their interactions with the events of the escaped prisoners. All 25 escapees were eventually found. Part B shares the much later recorded perspective of one of the escapees.

Note: The term Native American is typically used in political and academic matters. When Native Americans refer to themselves, they may use terms such as Indian, American Indian, First American, First Peoples, or Indigenous Peoples instead of Native American. At the time this text was written, the term Indian was commonly used, often without regard for individuals' self-identification.

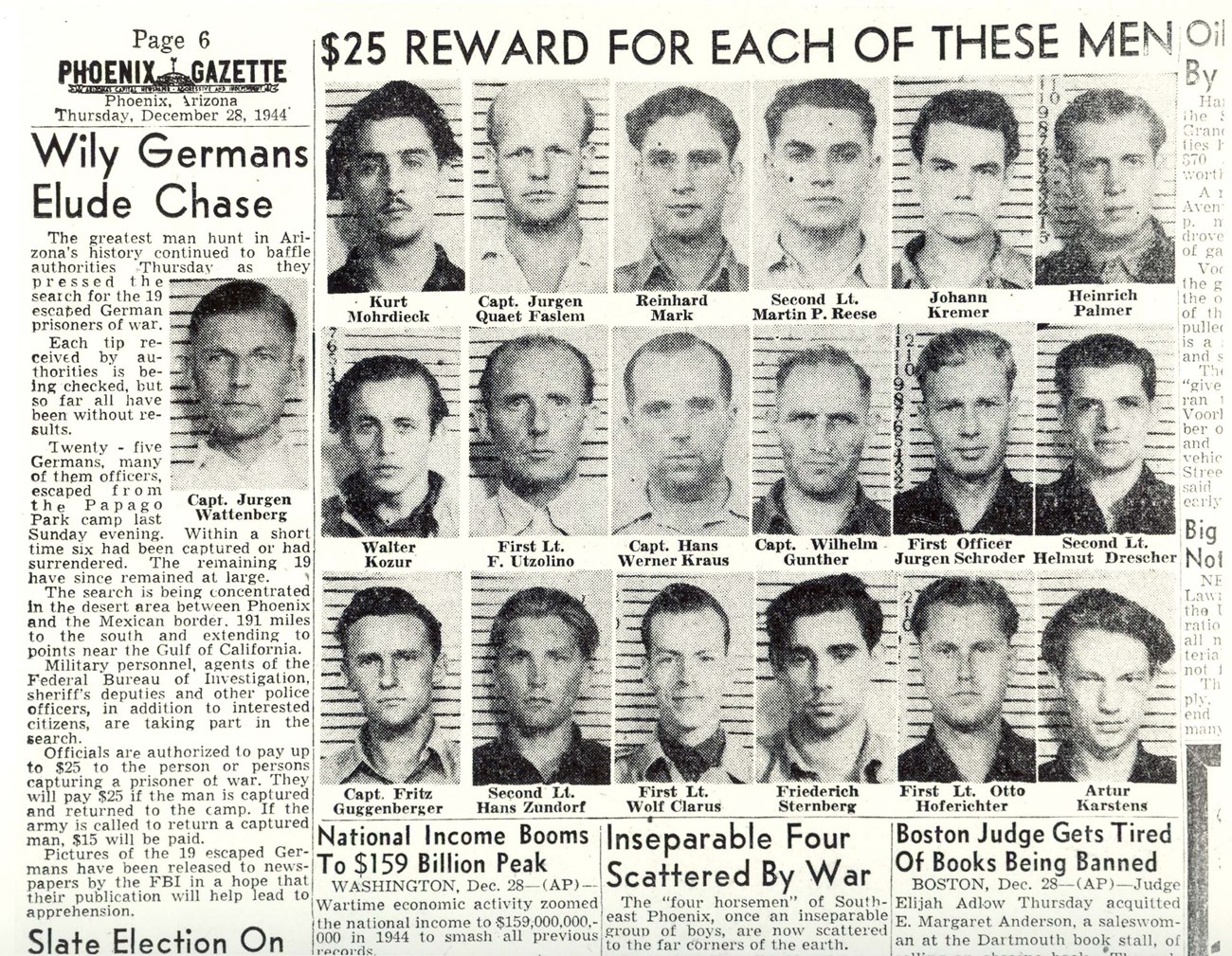

Question of Gestapo’s Part in POW Escape is Studied

February 1, 1945, The Buffalo News (New York)

By Oliver Pilat, Special to the Buffalo Evening News

Phoenix, Feb. 1 – Indians proved to be the nemesis of many of the 25 Nazi naval officers and submarine technicians who escaped Christmas Eve from the Papago Park prisoner-of-war camp near here.

The Indians, after whom the camp is named, occupy a reservation of 3,000,000 acres of largely desert land between Phoenix and the Mexican border.

Since it was assumed the escapees would head for the border, 200 miles away, the FBI tipped off the Papago chiefs that if they located a missing Nazi, they could collect $15 from the U.S. Army; if they captured one, it was worth $25.

A Papago woman, on Jan. 2, was the first to claim bounty for trapping two sturdy young submarine technicians.

Trackers Get Two

They were Henrich Palmer and Rheinhard Mark, near Sells, Ariz. Two days later near the same place, two more Nazis were recaptured by Fred Claymore and Dewey Jose, veteran desert trackers of the U.S. Indian Service.

Papagoes on Jan. 6 led U.S. Customs guards to two of Germany’s outstanding submarine aces. Senior Naval Lieut. Frederich Guggenberger, who sank the Ark Royal off Gibraltar, and Senior Naval Lieut. Jurgen Quaet-Faslen.

Since Arizona is a place where native white trackers often excel the Indians themselves, it was appropriate that the outstanding feat of the manhunt fell to Lieut. Theodore Stockton, an Arizona boy attached to the Florence POW camp.

Limp Aided Pursuer

He trailed Senior Naval Lieut. Otto Hoferichter and First Lieut. Hans Zundorf almost 100 miles through the desert.

Unlike the other escapees, Lieuts. Hoferichter and Zundorf wore recaptured shoes. But Lieut. Hoferichter had been reported limping before his escape: when Lieut. Stockton saw that limp on the ground he followed it all the way to Sasabee, near the border.

Everybody in Arizona joined the manhunt, from the highway patrol to the Civil Air Patrol, and from the woman sheriff's men to the ordinary citizen.

Once, when a couple of the fleeing Nazis blundered into a railroad section house west of Buckeye, a state hospital got bloodhounds on the trail, only to pull them off again under the mistaken impression that using such dogs was barred by the Geneva convention governing treatment of war prisoners.

Captured as Result of Slip

The story is still told in Arizona how two burly, travel-stained strangers, who spoke excellent English, went into a store in a small Arizona town and ordered a great quantity of groceries. ‘That will be 272 points,’ said the grocer.

The strangers looked at each other. ‘What are points?’ said one. Of course, they were escaped Nazis and were captured. Another strange slip was made by Martin Peter Reese and Jurgen Schroeder. When captured by Messrs. Claymore of the U.S. Indian Service they had 12 cans of milk, a slab of bacon, all stolen from the camp commissary, and a dozen cartons of chewing gum, which they had mistaken for rations.

All Surrendered Peaceably

None of the prisoners resisted when caught. Naval Lieut. Frederich Utzolino had been at liberty more than two weeks when he paused alongside an irrigation canal near the Gila Bend, Ariz., to strip and start washing his underwear.

A farmer looking for his hound, made the capture. Then Lieut. William Hill and some other men from a Papago Park patrol arrived and scored the neighborhood until they picked up two more Nazis.

The three Germans were planning to go down the Gila River on a raft to the border, not knowing that at the time of the year the river is dry and its bed nothing but deadly quicksand.

So it was, in twos and threes, that 22 of the 25 escapees were picked up, somewhat the worse for desert wear, and returned to Papago Park.

Did They Have Help?

Three weeks after the most serious break from a U.S. POW camp in this war, only the former camp spokesman and leader of the Nazis, Capt. Jurgen Wattenberg, one-time navigation officer of the Graf Spee, and two young Nazi zealots, Walter Kozur and Johann Kremer, still were uncaptured.

One question to be settled is whether the escapees had any important help from the Gestapo outside camp. Papago Park officials deny reports that some of the prisoners carried lists of addresses of people who might help them if contact, or had large quantities of genuine U.S. currency.

Several groups of escapees did have maps, Army maps and railroad timetable maps, but only those of the sort that might have been reclaimed from camp waste baskets, Papago Park officers declared.

Part B: Quotation from Heinrich Palmer, German Navy, Prisoner of War

Courtesy of Steve Hoza, from the book “PW: First-person accounts of German Prisoners of War in Arizona” (1995)

“At Papago Park, the US officers and the guard personnel always treated me fair and correct despite the trouble that our escape caused. From the things I’ve read, I have learned that our march through the desert was a real feat. My escape was an adventure for me. At that time I did not think about the dangers and what could have happened to me. As a youth, one is always optimistic and positively-oriented. I would like to add that none of us ever thought of sabotage or of harming any American citizens during our escape. It was pure youthful desire for adventure. I just wanted to leave the everyday life of a POW and try to reach a desired goal. What amazes me is that even 45 years later my escape is still of interest.”

Teacher Tip: Mature content is included in the opinion piece. Some language and descriptions may need to be discussed in advance with students. Encourage connections from this text to what was described in the oral histories in reading 1.

We Pamper War Prisoners While Germans Neglect, Starve Them

From “The Other Fellow’s Opinion” column in the Casa Grande Dispatch (April 13, 1945)

American armed forces now are getting far enough into Germany to begin finding Nazi prisoner of war camps. The Seventh Army came to the first one – a prison hospital somewhere near Heppenheim. The hospital was described by a war correspondent as a ‘living hell of starvation and filth – a factory of slow death for American prisoners of war.’ The correspondent further said records of the prison revealed 53 American soldier prisoners out of a total of 309 sent to the hospital in the last four months had died of starvation, infection, and lack of medical care. The others were described as walking skeletons

This press dispatch about the first German prisoner of war camps to be found by the western front forces reveals a situation of which every American should take cognizance. Especially should they take note of the fact that the wounds of prisoners of war or other nationalities were well cared for and they received adequate medical attention while our own boys were neglected – neglected and abused because of German hatred of Americans.

Contrast this picture of the first prisoner of war camp uncovered – no one knows what will be developed in other prison camps as they are located and American prisoners of war liberated – with the prisoner of war camps in this country. Serious thought should be given to charges that German prisoners of war are being pampered. But one conclusion can be reached and that is that we are again plain, unadulterated suckers of the first water.

As our armed forces find more of these Nazi hellholes, misnamed prison camps, Americans will realize more and more, the oft-repeated statements, that unless we treat German prisoners of war well our boys who are prisoners in Germany will be mistreated, are only excuses for pampering Nazi prisoners of war in this country.

German prisoners of war in this country have received the best of foods, equivalent to that which we supply for our own boys in service, and far better than the average American family has, what with rationing and shortages. Residents of this area will remember the 25 Nazis who escaped the prison camp in Papago Park last Christmas Eve who had supplied themselves with slabs of bacon, cigarettes and other hard-to-get items. We have never heard a satisfactory answer to the question where these Nazis obtained the things they had when they crawled through a tunnel in the Papago park camp. No one is so asinine as to believe they had them when they entered the camp. It never has been explained why the Nazis could dig this tunnel which took many weeks.

Americans are told German prisoners of war are well treated in this country because the Geneva convention requires it. That may be true, but certainly the Geneva convention doesn’t contemplate such excellent treatment as we have given to the Nazis. Actually, what has happened is that those to whom the job of caring for these prisoners of war was delegated, have been leaning backward in their interpretation of the convention rules under guise of the erroneous belief our boys will receive rough treatment. It is quite patent from this first prisoner of war camp found in Germany that the Germans haven’t paid any attention to the Geneva convention rules or any other rules except those dictated by hatred of Americans.

And what does this excellent treatment and pampering of German prisoners of war gain us? Belief, of all things, on the part of the arrogant, egotistical sneering Germans that we are afraid of them. A pretty kettle of fish. - Arizona Republic

Courtesy of Steve Hoza.

By the Numbers:

-

There were more than 500 Prisoner-of-War camps for over 400,000 Prisoners of War in the United States (mostly German).

- Example of German POW labor: In September 1944, approximately 200 German POWs from Papago Park began picking cotton. It was estimated that by October there would be 5,000 POWs available for work in cotton fields across the state.

Quotations to Consider:

“Colonel Barber’s answer to the problem (unrest and dissatisfaction among the prisoners) was, first of all, discipline – a German understands that probably better than any other man in the world – respect for the vanquished foe’s rights; creation of activities to take his mind away from his predicament and good meals. . . . Germany, our Army has learned, likewise is doing better by her American prisoners of war because of the reports neutral representatives are sending back on such camps as Papago Park. There is a method to this ‘madness.’”

-Fort Worth Star-Telegram, May 7, 1944

“It is full time that more stringent action is taken against the German prisoners who are now incarcerated in the state of Arizona. The constant stream of escapes from the prisoner of war camps is without excuse. It is outrageous that prisoners of war can escape from camp after camp, and that the commanding officers do not know that they are even missing from the camp, until some civilian or some peace officer reports that the prisoners who walked away from the camps have been recaptured.”

-Casa Grande Dispatch, February 16, 1945

Salt River Stories.

Student Activities

Questions for Reading 1, Quotations to Consider, By the Numbers, & Photos

-

Summarize: Describe what aspect of life at the camp is being described by the narrative piece(s) you read, along with details on their memories.

-

Prisoners mention many positive memories, such as activities and food served, or at least fair treatment. How do their oral histories challenge or confirm your understanding of life in a POW camp?

-

Focus on a narrative: Analyze Hans Lammersdorf’s reflections on the segregation they observed when arriving in the US. How does Lammersdorf describe the irony of American viewpoints and moral standings?

-

Synthesize: Use Reading 1, Quotations to Consider, and By the Numbers to describe the conditions at the Papago Park Camp, examples of work done by the prisoners, and relationships among prisoners, guards, and civilians.

-

What were some benefits and challenges faced by the local community of Tempe because of the camp?

Courtesy of Steve Hoza.

Questions for Reading 2

-

Who were different people and groups involved in the capture of the escapees? What skills did they have? What interests and incentives did they have to help?

-

Describe how the geography impacted the escape attempt.

-

What types of mistakes did the prisoners make that led to their capture? Why were they not prepared for some of the situations?

-

Use Henrich Palmer’s quotation. How did he reflect on his experience nearly 50 years later? What was the motivation for Palmer to escape?

Questions for Reading 3

-

According to the text, what was the condition of the American POWs discovered by the Seventh Army?

-

How did this compare to the description of the treatment of German POWs in the US?

-

Look back at the reading 1 oral history excerpts. From these examples, would you say the piece was based on fact, myth, or a mix of both?

-

What assumptions were made about German attitudes toward Americans, and how did this shape the writer’s argument?

-

How might the content and tone of this piece have influenced the American public opinion during the war? Discuss the potential impact of such articles on attitudes toward POWs.

Investigating Further:

-

Evaluate the ethical considerations behind how both the Germans and Americans managed their POW camps during the war. Consider the treatment of prisoners, adherence to the rules of the Geneva Convention, and the potential motivations behind each country's actions. To what extent do you think each upheld ethical standards, or were influenced by wartime biases? Support your response with evidence from the lesson readings.

a. Extension: Research perspectives, histories, and conditions at other United States and German POW camps to contribute to your response.

Lesson Closing

Answer the essential question: How did the presence of the Papago Park prisoner-of-war camp affect the city of Tempe?

Additional questions to consider:

What benefits and obstacles arose from housing POWs at Papago Park?

How did ethical standards guide the treatment of prisoners of war at Papago Park?

Additional Resources

Hoza, Steve. PW: First-Person Accounts of German Prisoners of War in Arizona. E6B Publications, 1995.

“Papago Camp Prisoner of War Camp” Map and History by Arizona State University

Tour of Papago Park POW Site, Document archived by Arizona Memory Project

This lesson was written by Sarah Nestor Lane, an educator and consultant with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.