Last updated: February 4, 2025

Article

Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 (Horse Creek Treaty)

NPS Image

NPS image

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, also known as the Horse Creek Treaty, was negotiated to legalize emigrant passage through Native American lands and to minimize violence and disruption caused by intertribal conflicts.

Leading Up to the Treaty

Since 1846, fur traders, Indian agents, mountain men, missionaries, and former U.S. Superintendent of Indian Affairs Thomas Harvey had been pushing for a conference to negotiate rights of passage through Native American lands for west-bound emigrants. The encroaching European-American population was competing with Native Americans for available resources, and the number of reprisals by both sides was mounting. Harvey argued that “a trifling compensation for this right of way” would secure peace between White emigrants and Native Americans.

Early in 1851, the Congress of the United States authorized holding a great treaty council with Plains Tribes to assure peaceful relations along the Overland Trails. Fort Laramie was chosen as the meeting place and various Native American tribes were summoned to arrive by September 1st. Over 10,000 Native Americans (men, women and children) gathered to sign this treaty. Fort Laramie could not accommodate the large numbers of attendees and their horses so the decision was made to move the council to the mouth of Horse Creek, 30 miles east of Fort Laramie near the present day Wyoming-Nebraska border.

Never before had so many Native Americans assembled to parley with White men. This was perhaps history’s most dramatic demonstration of the Plains tribes’ desire to live in peace.

Challenges

A shortage of grass for the thousands of attendee horses caused the parley to be moved downstream. Even in the new location the meeting had to be concluded before the grass at the new site had been consumed.

Tensions in the camp were high, mostly the result of fears of inter-tribal violence. Some of the gathering nations had long been hostile with each other and the tension between them was so strong that on at least one occasion it appeared that a disastrous battle was imminent. The efforts of Jesuit priest Pierre-Jean De Smet and others managed to calm the situation but distrust amongst the tribes led to segregated camps with the Native Americans using the U.S. officials and soldiers as a buffer.

Other challenges that attendees faced included: the delay of a 27-wagon supply train that was carrying provisions for the meeting; a cholera outbreak on the steamboat bringing supplies; reduced overall funding for the treaty; a military escort cut from 1,000 to 300 men; and a Cheyenne attack on a group of Shoshone that led to the death of two Shoshone men.

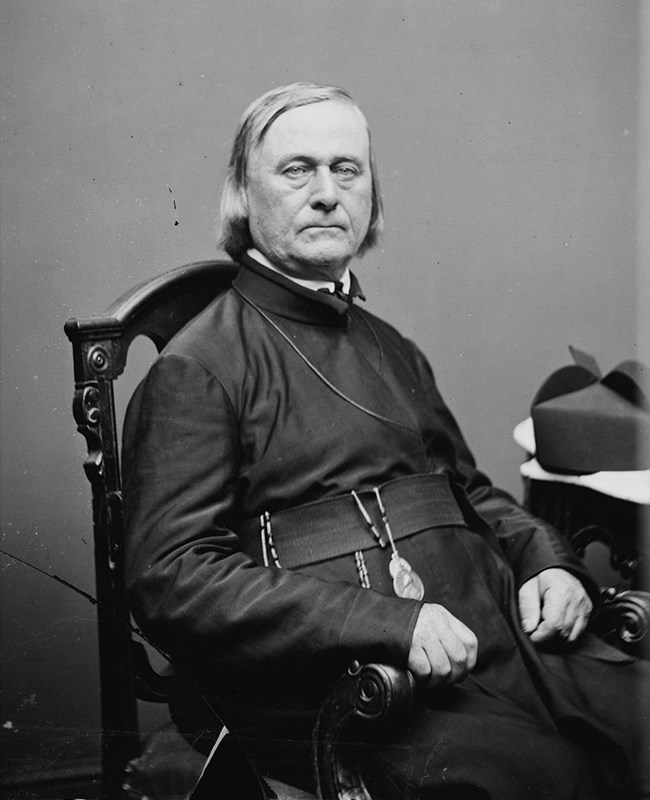

US Library of Congress

Attendees

Representing the U.S. Government were Thomas Fitzpatrick (long-time fur trader and Indian Agent) and David D. Mitchell (Superintendent of Indian Affairs at St. Louis).

Two notable Americans acted as translators:

- Jesuit priest Pierre-Jean De Smet who had 50 years of frontier experience translated for the Lakota who called him “Black Robe.”

- Mountain man Jim Bridger translated for the Crow.

The Tribal Nations who attended included: Oglala and Brule Lakota (represented by six chiefs), Cheyenne (four chiefs), Arapahoe (three chiefs), Crow and Assiniboins (each represented by two chiefs), as well as the Mandan and Hidatsa (combined represented by two chiefs.)

Others were invited but did not attend including the Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache. The Pawnee refused to attend after they were threatened with attack by the Lakota.

Critical Treaty Articles

Article 1: This was an attempt to create a “lasting peace” not only among U.S. citizens and Native Americans but also amongst the different tribes. Those who signed the treaty agreed to “peaceful relations amongst themselves... and agree to abstain in future from all hostilities whatever against each other, to maintain good faith and friendship in all their mutual intercourse, and to make an effective and lasting peace.”

Article 2: This gave the U.S. government the right to build roads through Native American lands and military posts along them for resupply and protection.

Articles 3 & 4: Established the responsibility of the U.S. to protect Native Americans from “all depredations by the people” of the U.S. committed against Native Americans and for the Native Americans to make restitution for the “depredations” committed by their own against the people of the U.S. in their respective territories.

Article 5: This article attempted to, for the first time, lay out on paper the territories claimed by the Tribal nations that showed up. Here, Father De Smet played a critical role as he was very familiar with the lands claimed by the Lakota. Jim Bridger played a similar role for the Crow. Contrary to what some believe, this article did not establish the reservation system, but it would be a step in that direction, finally becoming a reality with the ratification of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 (a second Fort Laramie Treaty). These territorial boundaries were quickly ignored by nearly all sides.

Article 7: This article promised that the U.S. would pay the Tribal nations $50,000 per year for ten years, with an option to extend this on a year-by-year basis for the following five years. This article has sparked some controversy as the original time was supposed to be for fifty years but before ratification Congress changed the length to ten years. From here, the treaty was supposed to go back to the original signers for them to approve the change before it became law. This has since led many to the conclusion that the U.S. meant to deceive the Native Americans, which might have some truth, but it is also an example of the challenges of communicating across cultures. The Native Americans believed that the men that showed up to negotiate with them had the final say, but they did not.

A digital image of the original Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, along with a transcript of the text can be found on the website of the National Archives.

Impact of the Treaty

The treaty was signed on September 17, 1851 but never ratified. Consequently, there has been some debate concerning its validity.

Almost immediately after the conclusion of the council, articles of the treaty were broken. While the Federal Government had promised to protect Tribal resources and hunting grounds from depredations by White settlers, it lacked the resources to enforce this obligation. In addition, only one of the promised annuity payments was ever made.

By 1864, Whites settlers demand for land pressured the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho into warfare, ending the hope for peace.

By 1868 relations between White travelers/settlers and tribal nations on the Great Plains had deteriorated to the point where the US Government once again decided to negotiate a treaty with Tribal peoples; in this case the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota, and Arapaho Nation. The result of these negotiations was the “Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868”.

NPS

Present Treaty Site

The Horse Creek Treaty roadside marker is located one mile west of Morrill, NE on Highway 26. Beyond the treeline about 2.75 miles in front of the marker, Horse Creek flows into the North Platte River.Learn more about efforts to designate the treaty site a National Historic Landmark.