Last updated: February 25, 2025

Article

Monarch Butterfly - Featured Creature

NPS/J. Ratchford

General Description

A flash of orange catches the corner of my eye. It’s a monarch! This handsome butterfly is relatively large (9–12 cm; 3.5–4.8 in), beats its wings slowly, and sports rich orange-colored, black-veined wings, edged in white spots. Its larval form—a caterpillar—is also brightly colored, banded in yellow, black, and white stripes. Males and females are similar, though males are slightly larger and have two roundish black spots on their hindwings that are specialized chemical producing scales.

The North American monarch (Danaus plexippus) breeds in the U.S. and is one of three species of monarchs—“milkweed” butterflies—found worldwide in the brush-footed butterfly family (Nymphalidae). While butterflies and moths are together in the order, Lepidoptera, they have differences. One is that butterflies typically have slender antennae ending in a rounded club, whereas moth antennae tend to be threadlike (filiform) or feathery (pectinate) without rounded tips.

Distribution and Habitat

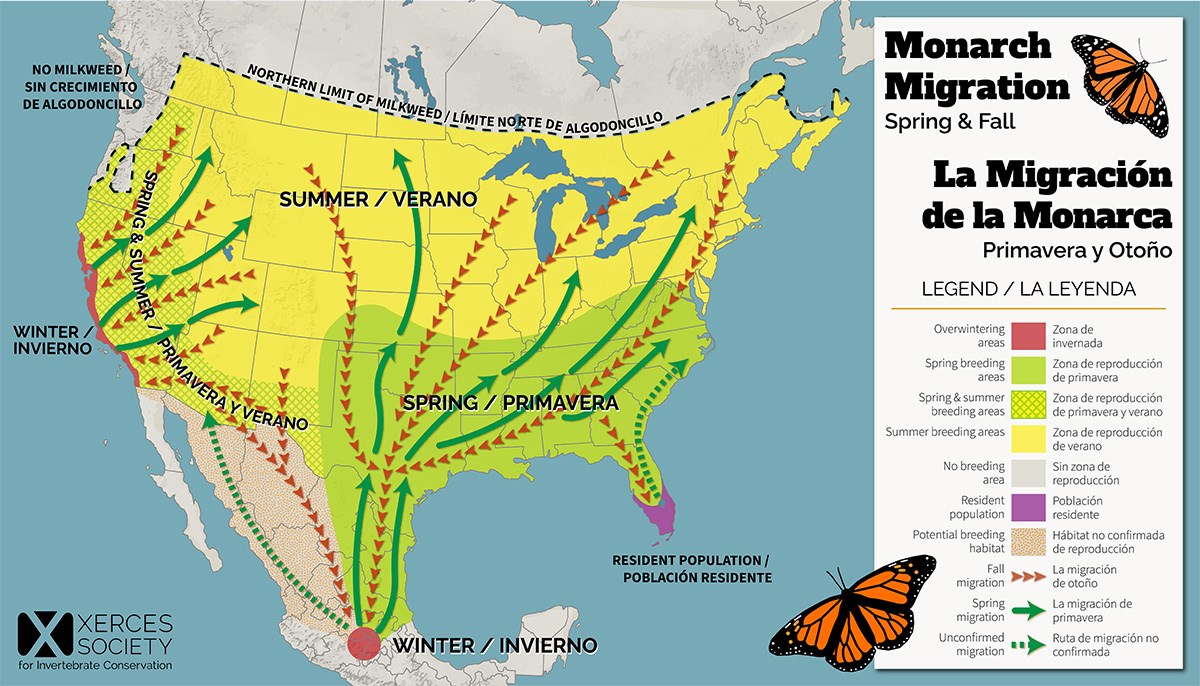

The western U.S. migratory population of monarchs, which is separated from the eastern U.S. population by the Rocky Mountains, breeds in most western U.S. states and winters largely along the California coast, down into Baja California, Mexico. The much larger eastern migratory population breeds throughout the eastern U.S. and winters in the central highlands of Mexico.

Monarchs forage in open habitat, such as fields, meadows, weedy areas, marshes, and roadsides in search of nectar. Breeding habitat is strictly tied to patches of milkweed (Asclepias spp.), whose leaves exclusively nourish their larvae. In winter, great clumps of migratory monarchs settle in moist forested groves with a mild climate, such as in coastal California or central Mexico. Here, they cluster for warmth and protection from wind and snow.

Behavior and Diet

Butterflies sense the world very differently than we do. Through chemoreceptors on their feet, butterflies can “taste” important molecules, like dissolved sugar or salt, on a plant. In this way, monarch females can detect the correct plant species on which to lay their eggs. Their antennae, along with fleshy labial palpi (sensory organs) on the head, are densely packed with chemoreceptors to detect the odor of nectar or male butterfly pheromones. Adult butterflies see color, including the special ultraviolet markings visible on some flowers and other butterflies, through compound eyes. Each eye aims at a slightly different angle to view up, down, forward, backward, and both sides at the same time. Two other senses partly explain the marvel of how monarchs navigate long-distance migration: sensing earth’s magnetism and sensing the direction of sunlight.

Through their straw-like proboscis (tongue), adult monarchs drink water and sip nectar from a variety of flowers, including thistles, daisies, sunflowers, clover, and more. Their caterpillar young have a clever dietary defense against predators. They eat only milkweed leaves, which contain toxic steroids call cardenolides. These steroids are distasteful and even toxic to predators like birds and mice. The toxins transfer to the adult during metamorphosis, protecting both stages of life.

Ecology

Spreading pollen as they sip nectar from flowers, monarchs are important pollinators. They are also food for birds, like jays. Most birds, however, avoid their bitter taste, warned off by the bright orange wings that signal poison. This bright color warning defense is known as aposematism. Black-headed grosbeaks (Pheucticus melanocephalus) have some tolerance for cardenolides and prey heavily on monarchs during the winter. It helps the birds that cardenolide loads decrease with monarch age, making the long-lived winter migrants more vulnerable.

Monarch larvae are much more vulnerable to predators. Beetles, true bugs, ants, spiders, and mice eat them, and fly and wasp parasitoids lay their eggs in the larva body, eventually killing it.

C. Schelz

Life Cycle

The astonishing long-distance migration of monarchs is rare in the insect world, involving up to a 3000 mile journey for eastern migratory monarchs. This epic journey to escape cold winters is the last stage of a multigenerational migration cycle that starts with a single egg laid on the underside of a milkweed leaf. The egg is laid after late winter mating and the journey north or inland has begun. The female will lay 300–500 eggs in the 2–5 weeks that she lives once she becomes sexually mature. To ensure enough food for each caterpillar, she typically lays just one egg per leaf. The egg hatches into a small eating machine that, in its later stages, can devour an entire milkweed leaf in 5 minutes! The caterpillar sheds its skin every 3–5 days to grow through five instar stages before forming a chrysalis. The pupa inside the chrysalis metamorphoses into an adult butterfly after 1–2 weeks. This journey from egg to adult can take as few as 25 days in warm temperatures.

Courtesy Xerces Society

After emerging as a butterfly, adults continue northward to summer grounds and repeat this short life cycle for about four generations into the late summer. Hormone changes in this last generation delay sexual maturity, allowing a “Methuselah” generation to live much longer (6–9 months) and make the long flight back to wintering grounds.

Cultural Significance

Día de los Muertos (Day of the Dead) celebrations in central Mexico coincide with the arrival of eastern migratory monarchs to their wintering grounds. Symbolically connecting the living with the dead—folklore claims that the souls of ancestors are carried in migrating butterflies—monarchs have been culturally important in Mexico for centuries.

Fun Facts

-

The long-distance “Methuselah” generation butterflies instinctively know how to find wintering grounds that they have never been to.

-

Butterfly scales are essentially tiny flattened hairs. The scales produce color by pigment or by diffracting light (metallic, iridescent colors) and can also produce pheromones for communicating with other butterflies.

Conservation

In December 2024, the US Fish and Wildlife Service proposed to list the monarch butterfly as Threatened under the Endangered Species Act. This was due to an estimated 80% decline in eastern migratory populations and a 95% decline in western migratory populations since the 1980s. A top threat is the loss of breeding, migration, and overwintering habitat. Another is insecticide and herbicide use, like glyphosate (as Roundup), that poisons milkweed and nectar sources. Shifts in habitat availability as the climate shifts also pose a threat.

Fortunately, this beloved butterfly benefits from several community science projects, like the Western Monarch Count and backyard pollinator gardens, among other conservation efforts (see the Community Science section below).

Where to See

Monarchs are mostly migratory through Klamath Network parks, though breeding has likely occurred in Lava Beds National Monument.

Learn More

- https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/monarch-butterflies-mexico-culture-conservation

- https://monarchjointventure.org/monarch-biology

Community Science Opportunities

Prepared by Sonya Daw

NPS Klamath Inventory & Monitoring Network

Southern Oregon University

1250 Siskiyou Blvd

Ashland, OR 97520

Featured Creature Edition: January 2025