Last updated: August 19, 2025

Article

Thomas (Tom) Shigekuni (1929–2019)

Courtesy of Vicki Shigekuni Wong

Turning Injustice into Action: A Life of Resilience, Service, and Legacy

Courtesy of Vicki Shigekuni Wong

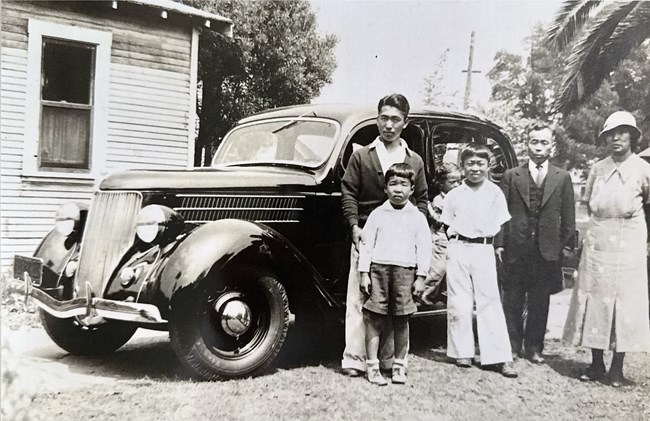

Thomas (Tom) Nobuyuki Shigekuni was born on August 4, 1929, in Los Angeles, California, to immigrant parents Frank and Shizuyo Shigekuni from Hiroshima, Japan. He grew up in the Seinan district of Los Angeles with his parents and two older brothers, Tunney and Henry, in a home rooted in faith, hard work, and quiet perseverance. His family operated several nurseries, including Inglewood Park Nursery on La Brea Avenue and another on 37th and Halldale.

Childhood Behind Barbed Wire

In the spring of 1942, following the attack on Pearl Harbor, Tom and his family were among the more than 120,000 Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes. Though his family had committed no crime, the FBI came to their home and cut the wires on their Philco shortwave radio to prevent them from “communicating with Japan.” They were first confined at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, a horse racetrack in Arcadia, California, before being relocated to Amache in Granada, Colorado. To young Tom, Amache felt like “the middle of nowhere.”

Courtesy of Vicki Shigekuni Wong

At Amache, Tom worked in the camp fields and helped his father prepare meals in the mess hall. He also recalled playing records at the block’s dance hall, where older boys would ask him to spin Glenn Miller’s slow tunes.

Though quiet by nature, Tom was never afraid to speak the truth. At thirteen, he revised the Pledge of Allegiance by adding, “liberty and justice for all… except us at camp.” When questioned by his principal about who had influenced him, Tom replied, “No one. I said it myself.” That same year, he wrote a school essay condemning the injustice of incarceration, an early glimpse of the lifelong advocate he would become.

Rebuilding a Life in Postwar America

After the war, his parents returned to Los Angeles, while Tom briefly joined his brother Henry in Elmhurst, Illinois. He later reunited with his family in Piedmont, California, where his mother worked as a domestic helper and his father as a gardener for a Chinese American family. Although the local school was just blocks away, Tom was told to walk several miles to attend another school so he would not be in class with his employers’ children.

Six months later, the family returned to Los Angeles. Tom graduated from Los Angeles Polytechnic High School in 1947.

One of his first jobs was aboard a tuna fishing boat out of San Pedro. He recalled signing up to fish, only to be designated as the cook once they set sail—even though he had never cooked before. He later assisted his father with gardening work for families in the upscale West Adams district of Los Angeles.

Military Service and Education

Tom received a personal scholarship to Pepperdine University from George Pepperdine himself, a fellow congregant at the Westside (Japanese American) Church of Christ.

During the Korean War, Tom enlisted in the U.S. Air Force. While stationed in Texas, he came across a Japanese American magazine featuring a photograph of Ruth Yamagishi from Oklahoma City. He and a few friends drove to meet her, sparking a friendship that grew quickly. Ruth later moved to Los Angeles and enrolled at Pepperdine University.

In 1952, Tom was deployed to Tokyo, where he served in Air Intelligence. He edited classified reports for Brigadier General Banfield, then head of intelligence in the Far East, which were forwarded to the Strategic Air Command in Omaha.

After completing his military service, Tom returned to Pepperdine and earned a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration.

Community Advocacy and Farmers Market Leadership

Tom went on to open Centrose Nursery in Gardena, which he operated for 36 years alongside his parents and his brother, Henry. In 1954, he married Ruth, and together they settled in Gardena—a Japanese American enclave of Los Angeles. While raising a young family and running the nursery, Tom also pursued a legal education. He graduated from USC Law School in 1966 and opened a law practice in Torrance, California.

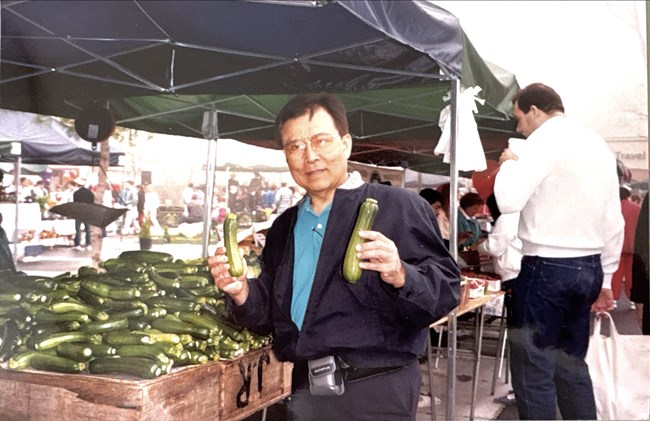

Courtesy of Vicki Shigekuni Wong

Tom’s professional and civic life blossomed at the intersection of justice, sustainability, and public service. In the 1970s, as the first Japanese American appointed to the California State Board of Food and Agriculture, he was asked to evaluate whether the state should continue its certified farmers market program. Tom was the only board member to conduct firsthand research, visiting markets across Southern California, interviewing farmers and shoppers, and compiling a detailed sociological and economic report.

His findings helped persuade the board to unanimously support the continuation of the program. That decision became a turning point in the preservation and expansion of California’s farmers market movement, one that thrives to this day.

Legal and Civic Contributions

As an attorney, Tom specialized in public service law, international contracts, elder care, and community development. His clients ranged from multinational corporations to aging individuals in need of advocacy. His dedication to community leadership extended far beyond his legal practice.

Tom served on numerous boards and organizations, including:

- Japanese American Citizens League (President, South Bay Chapter)

- Centinela Chapter, California Association of Nurserymen (Two-term President)

- Keiro Retirement Home (Board of Directors)

- South Coast Botanic Garden Foundation (Board of Trustees)

- USC Alumni Association

- Pepperdine Alumni Association (Board of Directors, three terms)

- Rotary Club of Torrance (Director)

- Los Angeles Energy Commission (Appointee)

- Amache Historical Society (Incorporating attorney and longtime board member)

He was especially devoted to preserving the memory of Amache. As one of its earliest and most committed advocates, Tom championed efforts to establish the site as a place of public learning and remembrance so that the stories of those incarcerated there, including his own, would never be forgotten

Enduring Legacy

Tom Shigekuni’s life was shaped by the injustice of incarceration, but defined by an unwavering commitment to justice, service, and community. He turned hardship into purpose and became a quiet force for change.

Through the years, he often warned that what happened to Japanese Americans during World War II could happen again. He believed it was not only possible, but imperative to remember. His voice joined those who urged vigilance, education, and truth-telling so that future generations might be spared such injustice.

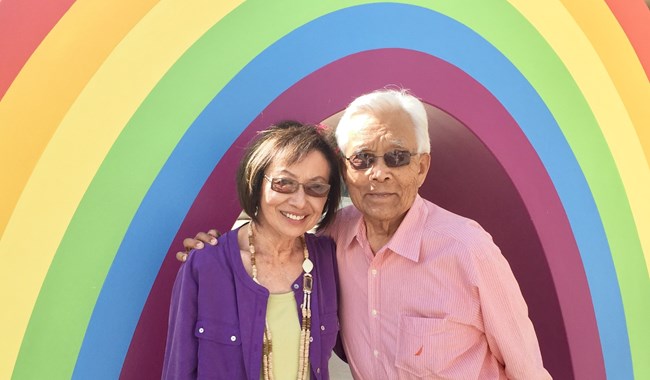

Courtesy of Vicki Shigekuni Wong

He also believed that one must live without regrets. And he did. In his final years, his last wish was to see the world—and he fulfilled it, traveling through both Asia and Europe for a month each. Even in his 80s, he remained curious, open-hearted, and unafraid to explore.

He passed away in 2019. A longtime resident of Palos Verdes Estates and dedicated member of the Redondo Beach Church of Christ, he is survived by his wife, Ruth, daughters Vicki, Cindy, and Leslie, and grandchildren Tiffany, Annie, Gabi, Joey, and Eli.

His story remains an enduring part of the Japanese American legacy and a vital thread in the remembrance of Amache.