Last updated: April 14, 2025

Article

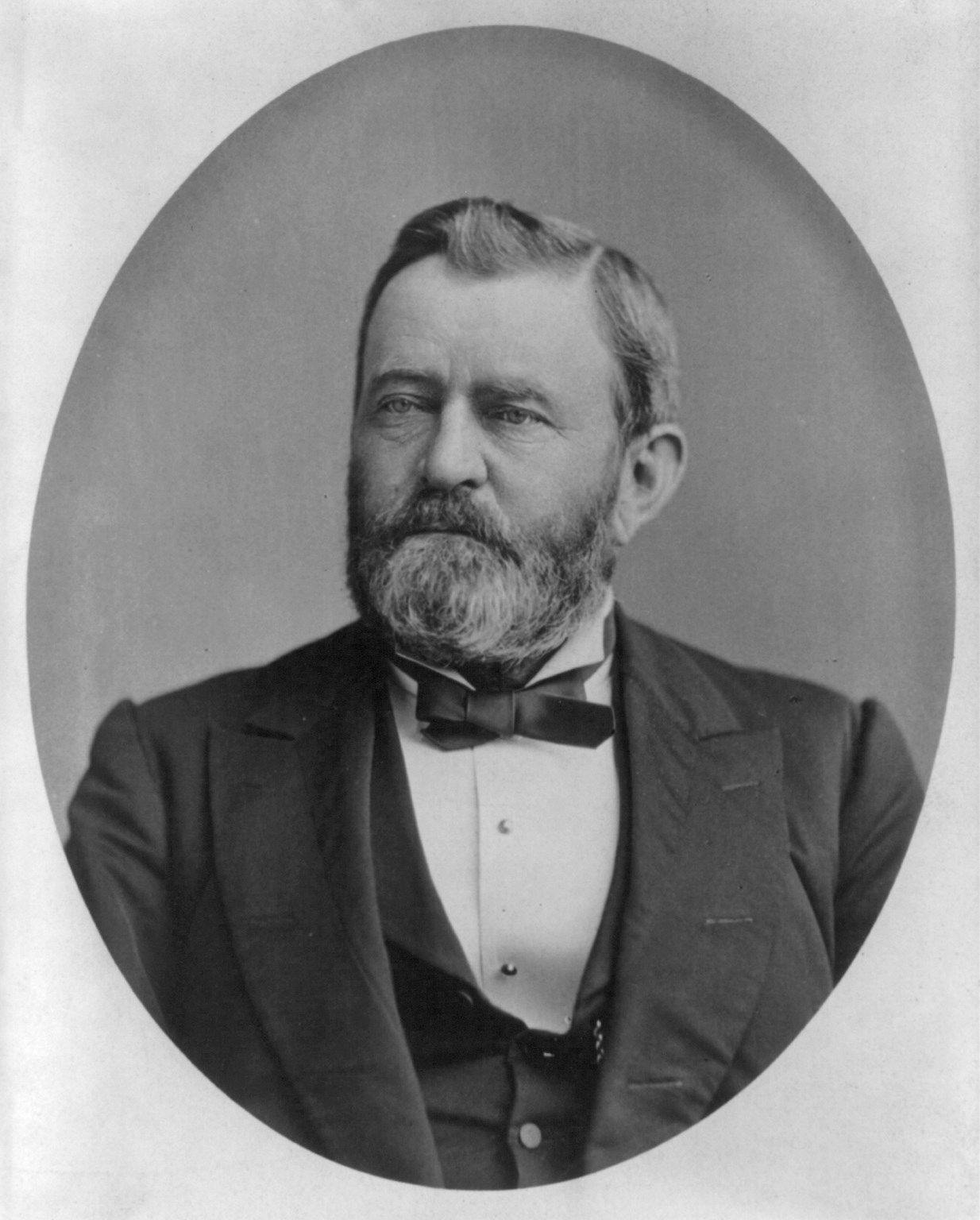

Ulysses S. Grant's Last Visit to St. Louis

Library of Congress

In his book Campaigning with Grant, Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter recalled a conversation with General Ulysses S. Grant during the 1864 Overland Campaign. Grant steered the conversation towards the future and stated his desire to move back to St. Louis after the Civil War. “I am looking forward longingly to the time when we can end this war, and I can settle down on my St. Louis farm and raise horses,” Porter recalled Grant saying. Military, political, and personal circumstances prevented Grant from becoming a permanent resident of St. Louis after the war. He still maintained connections to the city, however. Grant acquired full ownership of his father-in-law’s White Haven estate in 1866. He also visited St. Louis on 15 separate occasions between the war’s end in 1865 and his death in 1885.

Grant’s last visit to St. Louis occurred in 1883. His purpose was business related. While Grant had taken an active role in managing the farm operation at White Haven for most of his presidency, he decided to give up farming in the fall of 1875. He auctioned off his livestock and farm machinery, but held onto the property for the time being, choosing to lease it to a farmer named Henry Leis. In subsequent years Grant occasionally discussed selling White Haven and eventually hired the real estate firm of Cavender & Rowse. Edward D. Taylor, Deputy Collector of Internal Revenue in St. Louis, emerged as a potential buyer in the spring of 1883.

Emil Boehl/Missouri Historical Society

Ulysses and Julia Grant arrived in St. Louis on the evening of May 28, 1883. They stayed at the Southern Hotel at Fourth and Walnut Streets, which had recently been rebuilt after a fire destroyed the original hotel six years earlier. Grant “took dinner, after which he retired to his parlors and did not stir out all evening,” according to the St. Louis Globe-Democrat. The next day, the paper reported that “he had a number of visitors, who did not remain long, as the General retired early. He refused several invitations to dine out to-day, alleging that he came here to attend to business, and that he would not indulge in any pleasure until the business was consummated,” the paper claimed.

It appears Grant had only two meetings on May 29. He met with Cavender & Rowse that afternoon. While the exact nature of the meeting is unknown, an earlier letter from Grant indicates that there was disagreement about the method Taylor would use to purchase the property. Taylor proposed to make payments on the property gradually over several years, but Grant wanted to sell the property outright, offering a price of $100 per acre for 646 acres of land. Grant stated that he would welcome Taylor as a tenant, but only “if he will make the necessary repairs to the house, barns, & fences, and pay the taxes up to March [18]85.” Only then would Grant consider Taylor’s proposition if the property was not already sold outright within the next several years.

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

That same day, representatives from the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) made a call to Grant at the Southern Hotel. The GAR was the nation’s largest fraternal organization for Union veterans who had served in the Civil War and received an honorable discharge. By 1890, more than 400,000 GAR members lived in every state and territory within the United States. The GAR advocated for a variety of political initiatives, including pensions for Union veterans, “patriotic education” in public schools, and the erection of statues, monuments, and memorials to the Union cause.

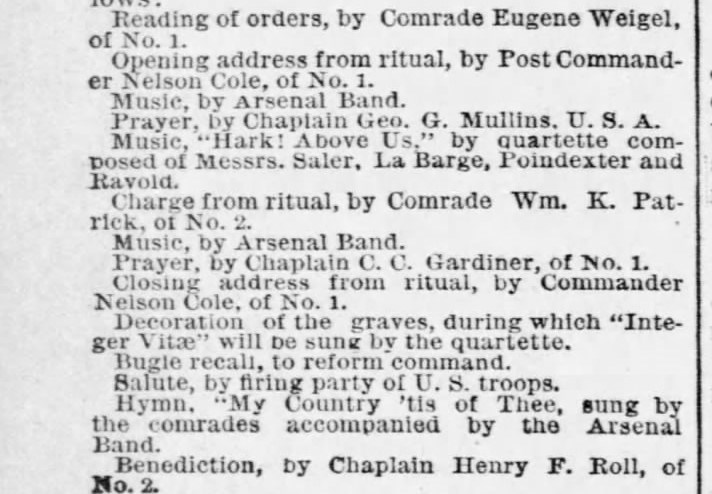

However, the organization was most known for its role in establishing Memorial Day (then popularly known as “Decoration Day”) as a cultural tradition. Starting in 1868, the GAR called upon Americans to decorate the graves of fallen Union soldiers in their local communities every year on May 30. While Memorial Day did not become an official federal holiday until 1971, local governments, businesses, and schools regularly took the day off during the 19th century. For the 1883 ceremony in St. Louis, the GAR asked Grant to attend a planned event at Jefferson Barracks, where he had started his army career 40 years earlier. When asked by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat about the GAR’s invitation, Grant responded, “I think I will go down with the boys to Jefferson Barracks.” Grant himself had been initiated into the GAR four years earlier as an honorary member of George Meade Post No. 1 in Philadelphia.

St. Louis Post Dispatch

The day’s events began in the city. Rain in the morning complicated matters, although a writer for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch later remarked that “the rain was appropriate . . . it was heaven’s tribute of tears to the honored dead.” The rain cleared in the afternoon, however, and by 1PM a large crowd had gathered at Locust and Sixth streets to begin the parade march. The parade was headed by members of three local GAR posts: the Frank Blair Post No.1, Gen. Lyon Post. No 2, and the Franz Hassendeubel Post No. 13. All GAR members carried a basket of flowers during the parade, and the Arsenal Band provided music. After an hour of steady marching towards the riverfront, GAR members boarded the steamer Centennial while attendees took three other steamboats, all bound for Jefferson Barracks.

Missouri Historical Society

Cannon fire greeted the GAR’s arrival at Jefferson Barracks around 3PM. The parade grounds were reported to be “in a miserable condition . . . slippery and treacherous” due to the morning rain, but a 28- or 38-gun salute (accounts differ) initiated the proceedings as all attendees made their way to the National Cemetery. For two hours there were speeches, prayers, and music. At 5PM GAR members began decorating the graves of all Union soldiers who died during the Civil War. By nightfall a total of 9,329 graves had been decorated. 5,000 people, including Ulysses S. Grant, had attended the day’s events in the city and Jefferson Barracks.

On May 31 the Grants had dinner along with 12 other guests at the house of Isaac H. Sturgeon, a prominent lawyer, politician, and railroad president, at 913 Garrison Avenue. Finally, on June 1 the Grants made their way to White Haven to further discuss their ownership of the property. While no record exists of how the day went, Grant’s efforts to close out business matters failed; the negotiations with Edward D. Taylor fell through and Grant remained the owner of White Haven. When the Grants departed St. Louis for Kentucky on June 2, they could not have known that it would be Ulysses S. Grant’s last visit to the city where he had started his army career, met his future wife, and started his family.