Last updated: February 4, 2025

Article

We Called Ourselves Combee: Freeing the Enslaved Along the Combahee River

Library of Congress

The Battle of Port Royal on November 7, 1861, resulted in the liberation of thousands of Gullah Geechee people on the Sea Islands around Beaufort, South Carolina. However, just a few miles up the nearby Combahee River, enslaved people continued to toil on rice plantations, building defenses and supplying food for the Confederate army. These enslaved African Americans who lived near the Combahee River in South Carolina called themselves “Combee” in the Gullah dialect.

The US Army sought to disable the Confederate’s river-based forces and cut off access to supplies by destroying the plantations along the Combahee River and liberating the enslaved laborers there. The Combahee River raid occurred on June 1-2, 1863, and was one of several freedom missions carried out by the U.S. Army and the United States Colored Troops (USCT) in the Sea Islands.

Library of Congress

Gathering Intelligence Before the Raid

The Combahee Raid was possible through the experiences of free and enslaved Gullah boatmen, freedom seekers, and Harriet Tubman. Gullah mariners traversed the rivers and creeks in South Carolina as they transported goods and information. Enslaved Combee people were aware of the location of sea mines (torpedoes) planted by Confederate soldiers in the 40-mile-long Combahee River, which posed a threat to the U.S. military boats on the water. After the Battle of Port Royal, plantation owners supported Confederate efforts to block access to the river. In some cases, they forced their enslaved laborers to construct and install barricades to block US Naval access on the river.

In May 1863, Francis Izzard, a freedom seeker from Colleton County who lived near the Combahee River, escaped and came to Beaufort. Francis Izzard provided the U.S. military with information about the locations of sea mines along the river and the locations of Confederate positions. Over time, more freedom seekers escaped from other islands and made their way to Beaufort, providing intelligence to the military and to Harriet Tubman about Confederate activity in the Lowcountry and the locations of their fortifications, guns, and encampments.

Harriet Tubman was not local to the Lowcountry. She was born enslaved in Maryland and liberated herself through escape and became a well-known conductor on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War. During the Port Royal Experiment, she volunteered to go to Beaufort to work as a nurse and cook for the US Department of the South. However, her connections to military officials gave her opportunities to begin her preferred work – that as a spy and scout. She began to recruit men to help carry out her work and strike at the heart of slavery. One of Tubman’s recruits was William Plowden, an African American man from Pennsylvania who enlisted in the USCT and was a scout, spy, and pilot. One night, Plowden and eight men sailed up the Combahee and returned to U.S. Army lines. They “reported on the bridges-trestle work, and the strength of the military guard of the enemy crossing.” With intelligence gathered from Tubman and her network of spies and scouts, the U.S. military created a plan to raid the plantations along the Combahee River.

Day of the Raid

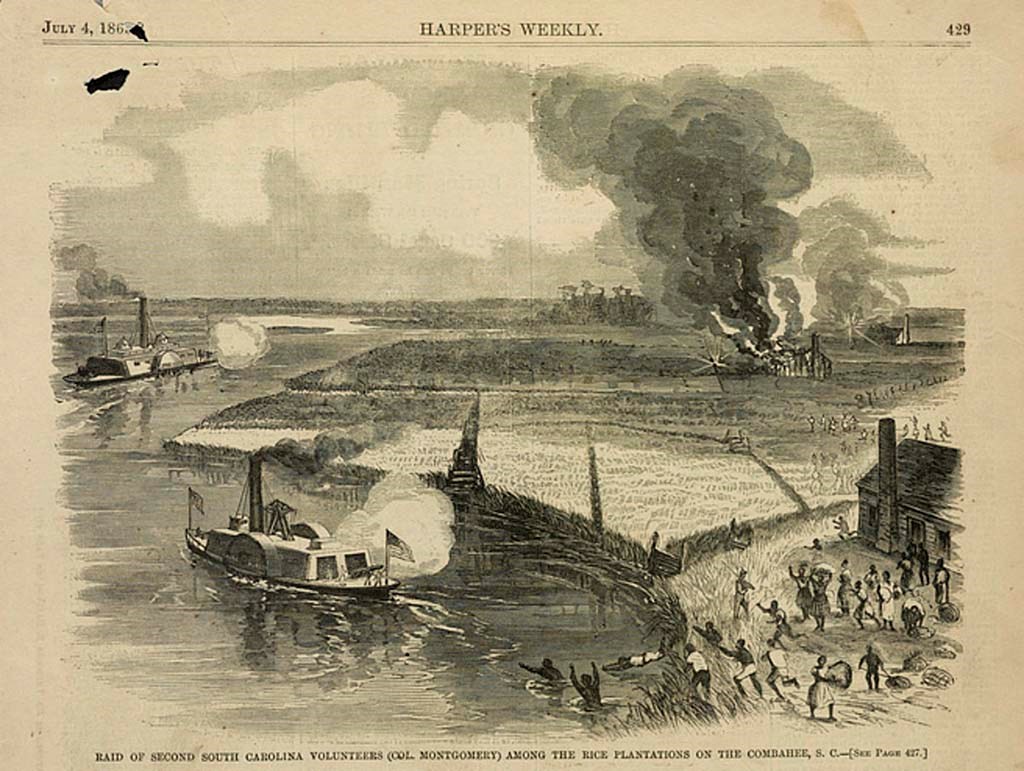

On June 1, 1863, 300 soldiers in the 34th USCT (2nd South Carolina Volunteers), the 3rd Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, Harriet Tubman, and Colonel James Montgomery departed the present-day Henry C. Chambers Waterfront Park in downtown Beaufort on board three gunboats, the Sentinel, John Adams, and Harriet A. Weed. They sailed north from Beaufort up the Coosaw River around the north end of Ladies Island. One of Tubman’s recruits, Isaac Hayward, a formerly enslaved boatman born near the Coosaw River, may have suggested reaching the Combahee by way of Coosaw, as opposed to the more open route through the St. Helena Sound. The Sentinel ran aground near present day Brickyard Point on the north end of Ladies Island, and the soldiers transferred over to the Harriet A Weed. The two remaining vessels continued on.

Early morning on June 2, the John Adams and Harriet A. Weed arrived at the entrance to the Combahee River at Fields Point, where Confederate soldiers fled the scene at the arrival of Black soldiers. Colonel James Montgomery left a company of soldiers at Fields Point, and proceeded towards Tar Bluff. When they reached Tar Bluff, it was abandoned, and a company established a communication line. Confederates attacked, but the Harriet A. Weed opened cannon fire on them, scattering the soldiers.

The raid continued from Tar Bluff to the Combahee River Ferry, present-day site of the Harriet Tubman Bridge on US Highway 17. Along the way, the soldiers under Montgomery’s command destroyed the plantation owners’ homes, rice mills, cotton gin, and a sawmill. All total, seven plantations were destroyed on the Combahee Raid. But more important than the destruction of Confederate property was the liberation of people. The enslaved Combee people heard the two boats coming a few miles away. The plantation overseers fled to safety, but the enslaved in the rice fields began to run and swim towards the two gunboats. Tubman helped organize their liberation by getting them onto the boats, and getting word to the surrounding plantations that freedom was at hand. By the time Tubman and the raiding party turned back towards Beaufort, more than 750 people were freed that day.

NPS/Elena De Marco

The Aftermath

In the days that followed, Tubman helped recruit more than 150 Combahee River freedom seekers to join the 2nd South Carolina Volunteers (34th USCT). Many of the refugees settled in camps around Beaufort, including at the site of Camp Saxton. When the war ended, Harriet Tubman returned home to Auburn, New York, where she spent the rest of her life fighting for the rights of Black women during Reconstruction, and arguing that her service on the Combahee River entitled her to a pension. Many of the Combees returned home to resume a life of rice farming along the river that once carried them to freedom.

In 2024, the commemorate the 161st Anniversary of the Combahee River Raid, Tabernacle Baptist Church dedicated a Harriet Tubman Monument on Craven Street, dedicated to the bravery, community, and resistance shown by Harriet Tubman and the freedom seekers on the Combahee Raid.

Sources

- Who Lived This History? The Combahee Raid - Lowcountry Africana

- Battle Unit Details - The Civil War

- The Combahee Ferry Raid | National Museum of African American History and Culture

- Combahee River Ferry & Harriet Tubman Bridge

- Fields-Black, E. L. (2024). Combee: Harriet Tubman, the Combahee River Raid, and Black Freedom during the Civil War. Oxford University Press. Chapters 13 and 14.

- Larson, K. C. (2009). Bound for the promised land: Harriet Tubman, portrait of an American hero. One World/Ballantine Books. Pages 212-217.

Tags

- harriet tubman national historical park

- reconstruction era national historical park

- combahee raid

- combahee river

- harriet tubman

- underground railroad network to freedom

- freedom seekers

- reconstruction era

- reconstruction

- reconstruction era national historic network

- reconstruction era national historical park

- south carolina

- civil war

- 2nd south carolina volunteers

- emancipation

- beaufort

- beaufort national historic landmark district