Part of a series of articles titled Cold War Civil Defense: From "Duck and Cover" to “Gun Thy Neighbor”.

Article

Nelson Rockefeller and Civil Defense

Rockefeller served within the Eisenhower administration as Special Assistant to President for Cold War Strategy, a position charged with developing tactical responses to the Soviets through psychological warfare and other means. In this capacity he had close involvement with the administration’s ongoing discussions on cold war military strategy and civil defense. A press photograph shows him participating in Operation Alert exercises of 1955, a nuclear evacuation drill of Washington DC and other cities that simulated the administration’s favored civil defense strategy at that time.

Leaving the administration to run for governor of New York in 1956, Nelson Rockefeller convened the Rockefeller Brothers’ Special Studies project, one of many task forces of influential experts he would assemble throughout his career to explore and propose solutions to national issues. A panel on the military included (in addition to his brother Laurance) Edward Teller, known as the father of the Hydrogen bomb, and Henry Kissinger, then a professor at Harvard University. Both Kissinger and Teller had a notably hawkish approach to nuclear strategy, favoring massive weapon stockpiling to counter the perceived Soviet military superiority and thereby deter a first strike on the US. They believed a Soviet nuclear strike could be survivable with shelters, and that the prospect of a prepared, protected civilian population would further deter such a strike. Kissinger and Teller also thought that shelters would engender a certain risk tolerance in the American public with respect to their military. In the words of the Gaither Committee, a task force which Rockefeller encouraged Eisenhower to assemble when exploring the costs and implications …a national shelter system would both protect the population and also “permit our own air defense to use warheads with greater freedom.”

Dissatisfied with Eisenhower’s decision to encourage discretionary private shelter building, Rockefeller attempted to influence civil defense policy from the state level. Upon being elected Governor of New York in 1958, Rockefeller convened a task force and then a committee to examine the prospects for civilian protection in the state. The report of the second of these, the State of New York Committee on Fallout Protection—framed civil defense (and nuclear strategy as a whole) in terms of fallout protection.

Survival in a Nuclear Attack, The New York State Civil Defense

Commission, 1960

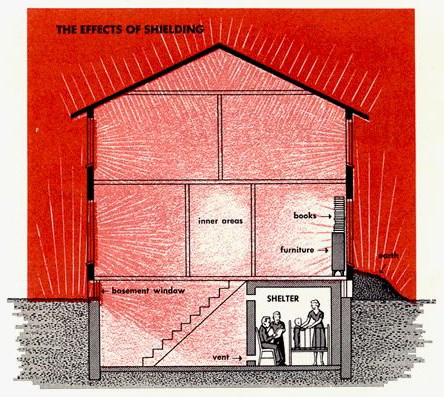

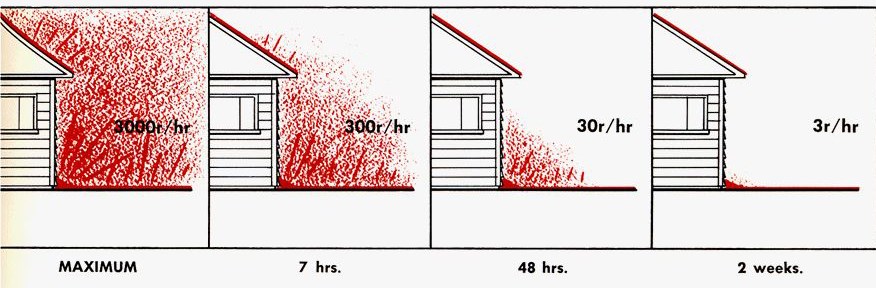

The recommendations of the New York State Committee on Fallout Protection were consistent with Eisenhower’s National Shelter Plan in that they placed the primary responsibility of shelter construction—of survival—on private citizens. Going beyond the federal initiatives that similarly sought to educate the public about fallout and encourage shelter construction, however, Rockefeller’s aimed to made shelter construction mandatory throughout New York State. All existing residences would be required to have a shelter with “minimum fallout protection” (a Protection Factor of at least 100, representing a 100-fold reduction in radiation on the inside) stocked for two weeks of habitation by July 1, 1963, and all new construction begun after January 1, 1962 would be required to a shelter. Inspection and enforcement of private shelter construction would be carried out at the local municipal level.

Unlike the federal educational materials that stressed the value of fallout shelters entirely as a means for saving the lives of individuals, Rockefeller’s committee report went into some detail describing the tactical advantages of a sheltered populace that were critical to the nation’s defense effort as a whole. “If our citizens, as individuals, take protective action against the threat of fallout,” it was explained, “it will be abundant notice to any potential enemy that we will not be forced by nuclear blackmail either to abandon our friends or to forsake our national interests at home or abroad.” Echoing Kissinger’s and Teller’s ideas, the promise that shelters represented of being able to withstand a first strike was believed to be as strategically important as the threat that the US nuclear arsenal represented in being able to launch one. A “well-prepared and safeguarded populace” who had fallout shelters would allow the United States to win a war by surviving attack, and could deter attack to begin with. It was the patriotic duty of civilians to make this happen.

Survival in a Nuclear Attack, The New York State Civil Defense Commission, 1960.

When Rockefeller introduced his shelter bill in a special address to the New York State Assembly in February 1960, the negative bipartisan reaction made it immediately apparent that it had no chance of passing. The following month, he presented a retooled bill with shelter construction made voluntary (and encouraged by tax breaks) that funded shelters in public buildings. Although costing a fraction of the mandatory plan, this second bill was met with “catcalls and jeers” in the Assembly before being tabled in committee. Having unsuccessfully pushed his fallout shelter agenda as far as he could at the state level, Nelson Rockefeller decided to address it with the next presidential administration in hopes that they would be more receptive than Eisenhower had been.

This text adapted from: Historic Structure Report: Mansion and Belvedere Nuclear Bombmb Shelters. Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park, Woodstock, VT. Written by Naomi Kroll Hassebroek, September 2018.

Last updated: August 5, 2019