Last updated: April 15, 2025

Article

USS HARTFORD (1858)

Courtesy Wadsworth Atheneum Musuem of Art

Building and Launching Hartford

In October 1857, Congress selected the Charlestown Navy Yard to build one of the United States Navy's new steam propeller screw sloops-of-war. With 24 heavy guns and a new steam propulsion system, it was to be a state-of-the-art ship of war. Named for the city of Hartford, Connecticut, USS Hartford had its keel laid in the shipways of Shiphouse H on January 1, 1858. Eleven months later, on November 22, the US Navy launched Hartford to much fanfare, with hundreds of spectators and workers crowding the shiphouse and piers to watch the spectacle. After the launch, Hartford entered Dry Dock 1 for a period as Navy Yard workers caulked the ship's hull and installed steam boilers and an engine built by the Boston-based company Harrison Loring.

Once fully outfitted, USS Hartford was commissioned on May 27, 1859, with Captain Charles Lowndes in command. Following its commissioning, USS Hartford embarked for the far east. It served as the flagship of the East India Squadron commanded by Flag Officer Cornelius K. Stribling. With US Minister to China John Elliott Ward aboard, Hartford visited Hong Kong, Guangdong, Shantou, and Shanghai in China and Manila in the Philippines on an important diplomatic tour to represent United States interests overseas.

Library of Congress

American Civil War - Admiral Farragut’s Flagship

With the attack on Fort Sumter sparking the American Civil War, USS Hartford was forced to return home. The ship departed the Sunda Strait in the Dutch East Indies on August 30, 1861, and reached Philadelphia on December 2. Early the next year, while in Delaware Bay, Flag Officer David G. Farragut, commander of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, selected USS Hartford as his flagship.

From the beginning of the war, United States naval strategy hinged on a successful blockade of the Confederate states, cutting them off from international trade. However, late in 1861, US high command decided on a more active strategy, with the capture of southern ports becoming a major objective. The largest port city in the Confederacy was New Orleans, and if the US Navy could capture it, they could link up with US Army forces advancing down the Mississippi River, effectively splitting the Confederacy in two. The strategy was termed the "Anaconda Plan."

After departing Delaware Bay on January 28, 1862, USS Hartford reached Ship Island, Mississippi, on February 20, which was to be the staging area for the attack on New Orleans. The first hurdle in the advance on New Orleans was the bar, a large, steep mud bank at the mouth of the Mississippi. After a month of effort, all but one of Farragut's ships had cleared the bar and began the assault on the city.

The Confederate defenses of New Orleans included two forts, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, along with three Confederate ironclad warships and a number of other vessels. When US Naval forces under Captain Henry H. Bell cut the boom chain, a heavy obstacle blocking access to the Mississippi River, sailors on USS Hartford lit a red lantern on the ship's mizzenmast, signaling the beginning of the advance to the rest of the fleet.

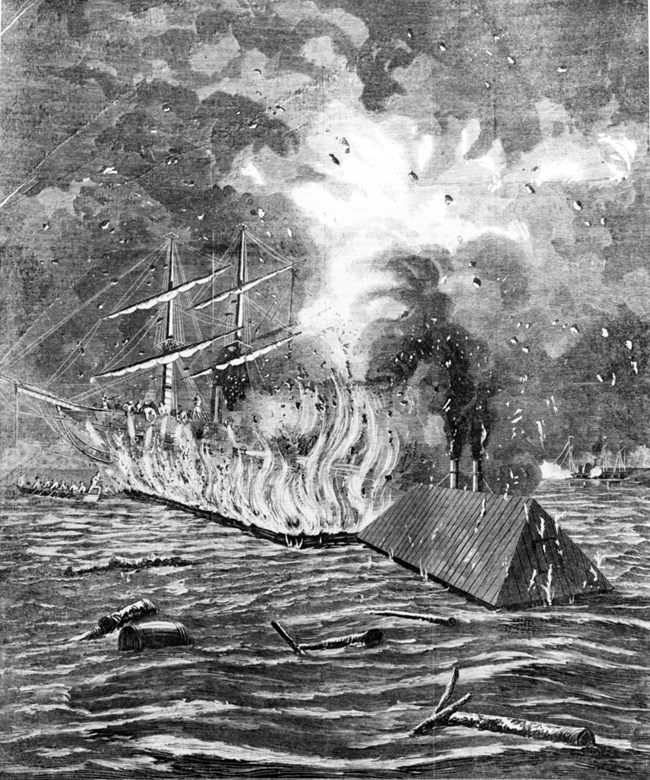

Harper's Weekly, 1862, U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command Photograph, NH 59074.

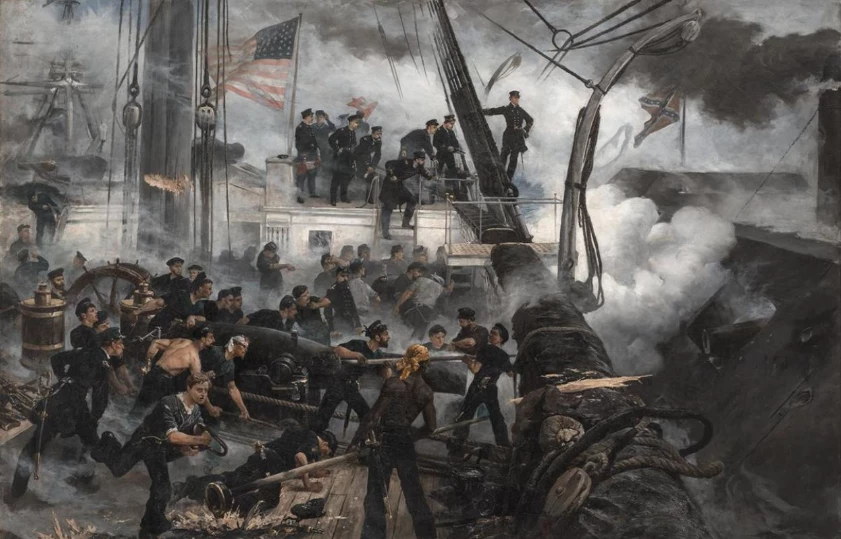

While Commander David Dixon Porter's mortar gunboats kept up a steady fire on the forts, Hartford engaged the Confederate vessels. Hartford maneuvered to dodge an attack from the ironclad CSS Manassas, then opened up a broadside which sank the Confederate tug CSS Mosher. A fire raft launched from Mosher struck Hartford, engulfing the ship in flames and forcing it aground within range of the guns of Fort St. Philip. A tense moment ensued as Hartford's sailors fought to extinguish the flames while returning fire on the fort. Once Hartford was clear of the riverbank and the fire was extinguished, the rest of the fleet was able to get past the fortifications and advance on the city.

United States forces occupied New Orleans without a fight. On April 29, Flag Officer Farragut landed along with marines from USS Hartford and took down the Louisiana state flag from City Hall. With New Orleans secured, US Naval forces advanced up the Mississippi, taking Baton Rouge and Natchez without resistance. The Confederate fortress city of Vicksburg was the next target, but the city, heavily defended by land and river fortifications, continually frustrated US efforts to capture it. On July 28, 1862, USS Hartford withdrew south and underwent repairs at Pensacola, Florida, before returning to New Orleans on November 9.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. LC-DIG-PPMSCA-33843

On March 14, 1863, Hartford ran the batteries at Port Hudson, Louisiana, encountering such heavy fire that only it and USS Albatross managed to get past. Hartford patrolled the Mississippi while General Ulysses S. Grant's Army of the Tennessee closed in on Vicksburg, capturing the city on July 4. With the Mississippi River under full United States control, Admiral Farragut turned his attention to Mobile Bay, Alabama, one of the last open Confederate ports on the Gulf coast.

Mobile Bay was heavily mined and protected by an ironclad, three gunboats, and two well-defended forts, making it a formidable obstacle to Farragut's fleet. From his position on USS Hartford, Farragut directed the assault on August 5, 1864. When the monitor USS Tecumseh struck a torpedo (the 19th century term for a naval mine) and sank, Admiral Farragut famously proclaimed, "Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!" and Hartford led the attack through the minefield. After three hours of fighting, the surrender of the ironclad CSS Tennessee ended the battle. With the surrender of nearby Fort Morgan a few weeks later, Mobile Bay was fully under US control.

The capture of Mobile Bay was one of the last large-scale naval operations of the American Civil War, as the fighting on land entered its final phase. USS Hartford departed for New York City on December 13, 1864, and underwent lengthy repairs before returning to sea in July 1865.

Postwar Pacific Tours

Following the Civil War, USS Hartford resumed its pre-war duties in the Pacific, serving as the flagship of the Asiatic Station Squadron from 1865 until August 1868, when Hartford returned to New York for decommissioning. Recommissioned on October 9, 1872, Hartford returned to the Pacific and served there until October 19, 1875. A few years later in 1879, the ship returned home, dry docking at the Charlestown Navy Yard. In June 1882, the steamer Virginian belonging to the British Leyland Line transport company collided with USS Hartford and a yard wharf. Thankfully, Hartford escaped major damage and both parties resolved the situation.

Later in 1882, USS Hartford became the flagship of the North Atlantic Squadron under the command of Commodore Stephen B. Luce. Hartford embarked on another tour of the Pacific, visiting Caroline Island, Hawaii, and Valparaíso, Chile, ending the tour in San Francisco, California, on March 17, 1884. After another Pacific cruise, Hartford was decommissioned again at Mare Island, California, on January 14, 1887. USS Hartford’s time as a ship of war had come to an end.

The End of Hartford

USS Hartford spent nine years at Mare Island, from 1890 to 1899. From 1894 to 1899, the ship underwent a major rebuilding effort. On October 2, 1899, Hartford was reactivated and transferred to the Atlantic, this time to serve as a training vessel for midshipmen. Hartford served this purpose until October 24, 1912, when it was transferred to Charleston, South Carolina, to serve as a station ship.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress. LC-Lot-3305-18.

Hartford was yet again decommissioned on August 20, 1926, before transferring to Washington, D.C., on October 18, 1938. On October 19, 1945, Hartford travelled to the Norfolk Navy Yard, which would be its final station. Attempts to transform USS Hartford into a museum ship fell through, and the ship was sunk and dismantled on November 20, 1956.

USS Hartford served at the forefront of some of the most consequential naval campaigns of the American Civil War as the flagship of one of the most famous naval officers of the conflict. From its launching in 1858 at the Charlestown Navy Yard until its sinking in 1956, Hartford was at sea for nearly 100 years. Though the ship itself no longer exists, components of Hartford still stand as relics and are on display in locations across the country.

Contributed by: Raphael Pierson-Sante, Digital Content Support Volunteer

Sources

“Hartford I, 1859-1956,” Naval History and Heritage Command, September 28, 2015. https://www.history.navy.mil/research/histories/ship-histories/danfs/h/hartford.html

Frederick R. Black and Edwin C. Bearss. The Charlestown Navy Yard 1842-1890, National Park Service, 1993.