Last updated: March 18, 2025

Article

Hannah Van Buren

Library of Congress

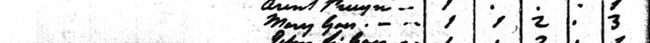

Hannah Van Buren, wife of the eighth President of the United States, Martin Van Buren, was a woman of quiet strength and deep compassion. Born on March 8, 1783, in Kinderhook, New York, she was the daughter of Johannes Dirckson Hoes and Maria Quackenboss. She grew up in a close-knit Dutch community, where Dutch was commonly spoken in households, including her own. Among her childhood companions was her cousin and future husband, Martin Van Buren, with whom she shared a lifelong bond. After Johannes Hoes passed away suddenly in 1789, Hannah’s mother headed a household and enslaved at least three people, as recorded in the 1790 census.

In February 1807, Hannah and Martin secretly married in Catskill, New York. The couple travelled twelve miles during the harsh winter to the home of Hannah's sister for the ceremony. Their union was marked by the births of five children: Abraham (1807), John (1810), Martin Jr. (1812), Winfield Scott (1814, who passed away shortly after birth), and Smith Thompson (1817). Their family life was one of transitions, moving first to Hudson, New York, in 1808 when Martin became a surrogate for Columbia County, and later to Albany in 1815 following his election as New York’s Attorney General.

National Archives

It was in Albany that Hannah's life took a tragic turn. She contracted tuberculosis, a disease that was often fatal in the early 19th century. She endured a prolonged illness and ultimately passed away in 1819 at the young age of thirty-five. Her death left Martin a widower, and he never remarried.

While Martin Van Buren went on to hold the nation’s highest office, Hannah’s memory was cherished by those who knew her. Family accounts depict her as a woman of profound humility and kindness. In 1868, Angelica Van Buren, Martin’s daughter-in-law, sought to gather memories of Hannah for a memoir. She turned to Christina Cantine, Hannah’s niece, who provided an account later included in Laura C. Holloway’s The Ladies of the White House (1881). In her recollections, Christina described Hannah’s gentle demeanor, her nervous disposition during her illness, and her final moments, in which she called her children to her bedside, offering them her blessing with remarkable composure. Even in death, Hannah’s selflessness shone through—she requested that the money typically spent on funeral scarves for pallbearers be instead donated to the poor.

"Aunt Hannah lived but a short time after their removal to Albany, dying at the early age of thirty-five, when her youngest child was still an infant. I can recall but little about her till her last sickness and death, except the general impression I have of her modest, even timid manner – her shrinking from observation, and her loving, gentle disposition. The last, long sickness (she was confined to the house for six months) and her death are deeply engraved on my memory. When told by her physicians that she could live, in all probability, but a few days longer, she called her children to her and gave them her dying counsel and blessing, and with the utmost composure bad them farewell and committed them to the care of the Saviour she loved, and in whom she trusted. This scene was the more remarkable to those who witnessed it, as, through the most of her sickness, she had been extremely nervous, being only able to see her children for a few moments on those days on which she was most comfortable. They could only go to her bedside to kiss her, and then be taken away. As an evidence of her perfect composure in view of death, I will mention this fact. It was customary in that day, at least it was the custom in the city of Albany, for the bearers to wear scarfs which were provided by the family of the deceased. Aunt requested that this might be omitted at her burial, and that the amount of the cost of such a custom should be given to the poor. Her wishes were entirely carried out”

- Christina Cantine, Laura C. Holloway’s The Ladies of the White House, 1881

Despite her influence within the Van Buren family, Hannah was notably absent from Martin Van Buren’s autobiography. Nevertheless, her legacy endures through the accounts of those her cherished her memory, painting a portrait of a woman whose grace, kindness, and quiet strength left an indelible mark on those who knew her.