Last updated: February 12, 2025

Article

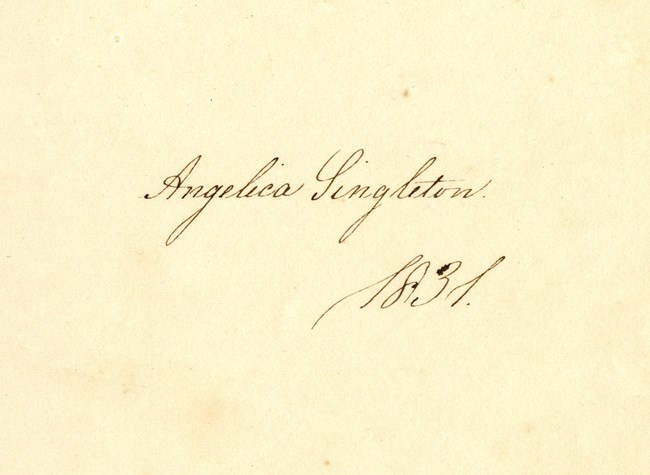

Angelica Singleton Van Buren

White House Historical Association / White House Collection

Early Life, Elegance, Influence and Criticism

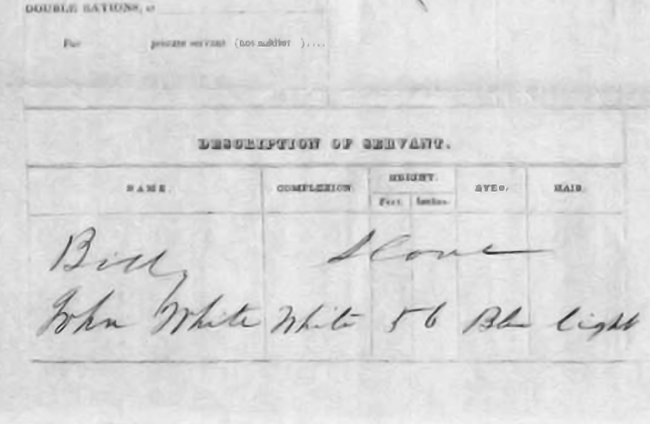

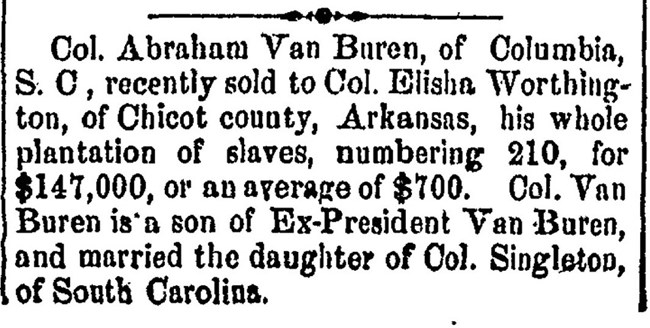

Angelica Singleton Van Buren wasn’t just a figure of history—she was a young woman navigating a life that blended privilege, responsibility, and public scrutiny. Born in 1818, Angelica grew up in what she perceived as the luxurious, plantation-filled world of South Carolina’s Singleton family, a life built on the forced labor of enslaved people. Her upbringing in this southern aristocracy as well as her education at Madame Grelaud’s French School shaped her into someone accustomed to influence and refinement.Her meeting with the Van Buren family was not by chance but rather thanks to her cousin, the legendary former First Lady Dolley Madison. Through this connection, Angelica met and married Abraham Van Buren, the eldest son of President Martin Van Buren, in November of 1838. Their wedding, held at her family’s estate called Home Place in South Carolina, symbolized a union between northern and southern elite families, and it was celebrated as a high-society event of the time. The couple’s honeymoon in London gave rise to her fascination with European culture and solidified their romantic partnership.

University of South Carolina. Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections

Angelica Van Buren’s time as White House hostess was as much about navigating the tides of a changing America as it was about her personal refinement. Her upbringing and education had prepared her to bring an air of dignity and sophistication to the White House, and she saw her role as more than ceremonial. Angelica positioned herself—and other women in the administration—as influential figures in the social and political dynamics of the time. But in an era marked by economic struggles, her polished elegance became a double-edged sword.

While Angelica tried to navigate the complexities of being White House hostess the couple’s first child, Rebecca, was born in 1840. Tragically, Rebecca passed away in infancy, a loss that cast a shadow over their early years as parents. The Van Buren family’s public life, particularly Angelica’s role as the de facto First Lady, demanded grace in the face of personal loss.

As the country weathered an economic depression, Angelica’s efforts to elevate the White House’s image were met with mixed reactions. Her desire to enhance its grandeur, including rumored plans to redesign the grounds in the style of European royal gardens, became a lightning rod for criticism. Political opponents seized on this narrative, with Whig Congressman Charles Ogle famously delivering his scathing "Gold Spoon" speech. He painted the Van Buren administration as extravagant and disconnected, accusing them of living in a royal fashion far removed from the realities of everyday Americans.

This criticism didn’t stay confined to Angelica—it became a symbol of everything opponents claimed was wrong with Martin Van Buren’s presidency. In the contentious 1840 election, the image of the Van Buren household as aristocratic and aloof played a significant role in his defeat. For Angelica, the grace and sophistication that had initially charmed Washington now seemed to embody the very disconnect people resented.

Her story is a vivid example of the fine line between style and substance in public life. Angelica started her tenure admired for her elegance and polish, but the political and social pressures of a struggling nation turned those same qualities into liabilities. It’s a reminder of how quickly public perception can shift, especially in a time of economic hardship and changing societal values. For Angelica, navigating these expectations became a defining—and ultimately challenging—part of her legacy.

Library of Congress

Life After The White House: Lindenwald

After Martin Van Buren’s defeat in the 1840 election, Angelica’s life transitioned from the grandeur of the White House to a quieter yet still prominent role at Lindenwald, the Van Buren family estate in Kinderhook, New York. Though no longer the official White House hostess, Angelica remained a central figure in the family’s social and political sphere, continuing to entertain visitors and maintain the refined standards she was known for. Lindenwald became a hub for Van Buren’s post-presidency activities, and Angelica’s charm and graciousness helped preserve the family’s social stature during a brief period of relative seclusion from national politics.Angelica’s connection to her mother, Rebecca Travis Coles Singleton, played a critical role in shaping her approach to domestic management and hospitality. Raised in the plantation culture of South Carolina, Angelica likely absorbed many of her mother’s techniques for running a large household, knowledge she relied upon during her years as a hostess both at the White House and at Lindenwald, her father-in-law Martin Van Buren’s estate in New York.

In a letter to her mother, Angelica revealed both her dependence on Rebecca’s expertise and her own meticulous attention to detail in managing a household:

"First I want you to send me a list of supplies such as you usually send to Charleston in the Fall when the house is out of everything. I want it as a guide in ordering groceries etc. for Lindenwald & I have but an imperfect idea of the quantities of sugar etc. especially for six months’ consumption with a regular family of four & I fear a great deal of strange company stopping by all through the summer en route to Saratoga etc. & to see the President & Smith & John & various other friends on long visits."

In this letter, Angelica expressed her uncertainty in managing the scale of provisions needed for a Northern household while hosting frequent visitors—a challenge compounded by her role as the primary female presence at Lindenwald.

She turned to her mother not only for advice on supplies but also for something deeply personal and practical: the copying of her recipe book. She wrote,

This request highlights Angelica’s reliance on her mother’s culinary knowledge to maintain the hospitality expected of her, whether entertaining visiting dignitaries or managing everyday meals.“Then I want to get you to have your Recipe book copied in full & all your little stray recipes which you know to be good.”

Angelica’s duties at Lindenwald extended far beyond hosting. As the de facto head of the household, she was responsible for keeping the estate in order, ensuring its smooth operation in a way that only a woman of her experience could. She humorously described the alternative—her absence—as leaving Lindenwald vulnerable to “Bachelor missrule.” This observation suggests not only her indispensable role in the household but also her understanding of the contrast between the orderliness of a woman’s touch and the perceived chaos of an all-male environment.

These letters reveal the close bond Angelica shared with her mother, a relationship rooted in shared knowledge, trust, and reliance. Rebecca Singleton’s guidance from South Carolina extended beyond simple recipes or lists of provisions—it symbolized the continuity of Southern domestic traditions that Angelica carried with her to her new life in the North. This connection to her mother, and to the Southern ideals of hospitality and household management, defined Angelica’s ability to navigate her dual roles as White House hostess and matriarch of Lindenwald.

At Lindenwald, Angelica found solace and joy in the growing Van Buren family. She and Abraham welcomed three sons—Singleton, Martin, and Travis—each bringing light and love into their home. But motherhood in the 19th century was not without its heartache. In July of 1843, Angelica suffered a miscarriage, a painful reminder of the fragility of life during that time. Despite the comforts of their privileged position, the Van Burens were not immune to the profound emotional toll of loss. The strain it placed on their hearts was ever-present, yet Angelica carried on, her strength as a mother shining through even in her grief.

Amid the emotional and physical challenges of motherhood, the flow of visitors to Lindenwald never ceased. Angelica, ever the gracious hostess, leaned on the help of her step-niece, Mary MacDuffie, to assist with the duties of social life. In a letter to her mother, Angelica affectionately noted,

This playful comment highlights the warmth and closeness within the family, despite the pressures Angelica faced. In moments like these, Angelica's ability to find lightness in her world, even amid sorrow, paints a portrait of a woman who, while deeply human, carried herself with remarkable grace and resilience.“It amuses me to hear that the EX takes her for his partner (at cards) frequently & still more surprising to hear never scolds.”

At Lindenwald, Angelica adapted to the rhythms of rural life while balancing her responsibilities as a mother and wife. Her role as hostess shifted to a more intimate scale, focusing on hosting family gatherings, local dignitaries, and political allies who still sought Martin Van Buren’s counsel, or to provide support for him in his election campaigns of 1844 and 1848. Despite the loss of the formal stage the White House provided, Angelica’s sophisticated influence remained evident, as she brought the same elegance and organization to Lindenwald’s social life, ensuring the estate reflected the Van Buren family’s legacy of leadership and refinement.

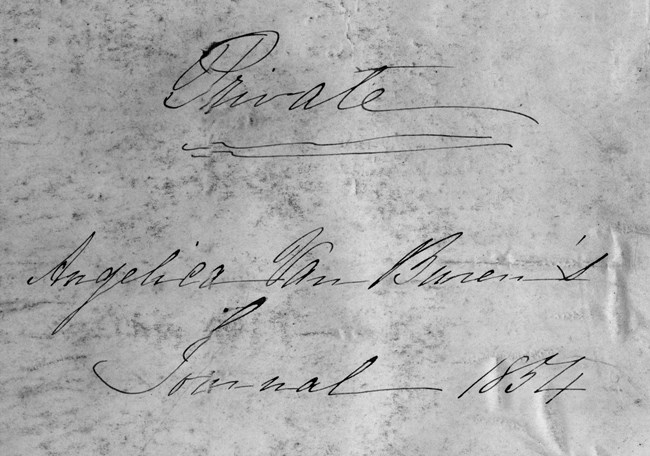

Angelica Singleton Van Buren Journal Volume I /

University of South Carolina. South Caroliniana Library

Evolving Worldview and Contradictions

In the mid-1850s, Angelica embarked on a transformative journey through Europe, where she encountered reform movements advocating for better conditions for laborers. These new ideas began to shape her perspective, but it was a heartbreaking revelation within her own family that truly opened her eyes to the vulnerabilities women faced. Her sister endured physical abuse and financial exploitation at the hands of her husband—a harrowing experience made worse by the fact that, as a woman, she had no legal rights to protect herself. This painful reality left a lasting mark on Angelica, stirring a deeper awareness of the inequities women and other marginalized groups faced.

Presumed to be Public Domain

Kinderhook Herald / NY Historic Newspapers

Even as the country fractured during the Civil War, Angelica’s southern identity endured. She sent blankets to Confederate soldiers imprisoned in the North and maintained her loyalty to southern relatives, revealing the deep roots of her upbringing. Angelica was, in many ways, reflective of her time—a woman of charm, refinement, and privilege, grappling with the social and moral tensions of 19th-century America.

Family Historian and Keeper of the Memories

Angelica’s correspondence with Christina Cantine, President Martin Van Buren’s niece, after the Civil War sheds light on her role as a family historian and her enduring connection to her husband’s lineage. Their letters reveal Angelica’s active interest in preserving the memory of Hannah Van Buren, Martin Van Buren’s late wife, who had passed away long before his presidency. Angelica reached out to Christina in a letter that is both practical and heartfelt, asking her to contribute to a memoir being compiled about the wives of American presidents.In her letter, Angelica explains that Mrs. E. F. Ellet, author of Women of the Revolution, was preparing a publication titled Memoirs of the Wives of Our Presidents. She writes,

Acknowledging her own limitations in recounting Hannah’s life, Angelica expresses confidence in Christina’s ability to provide meaningful details, saying,“Mrs. Van Buren died when her children were so young that I believe they remember but little more about her than I know myself, & I only know that which Mr. Van Buren related to me from time to time.”

Her request reflects not only her desire to ensure Hannah’s story is preserved but also her respect for Christina’s role as a keeper of family memories.“I can think of no one more likely than you to possess the desired information.”

Their relationship appears to have been warm and familial. In another letter, Angelica sent Christina a box of wedding cake from her niece Anna Van Buren’s marriage to Edward Alexander Duer, along with a copy of The Ladies of the White House, which included a memoir of Hannah Van Buren. She gently reminded Christina of a previous contribution:

These thoughtful gestures illustrate Angelica’s commitment to maintaining close ties with extended family while taking active steps to celebrate and document the lives of those in the Van Buren legacy.“The little sketch of her which you probably remember having written for one a year or more ago in response to an application for information about her from other parties.”

Through these letters, Angelica’s personality shines—pragmatic yet warm, determined to honor her family’s history while fostering personal connections. Her exchanges with Christina highlight her role not just as a political hostess but as a custodian of memory, deeply invested in preserving the narrative of her family for future generations. However, Angelica’s legacy is as complicated as the era she lived in. Her life offers a glimpse into the contradictions of antebellum society, where individuals could embrace ideals of elegance and progress while simultaneously benefiting from and perpetuating injustice. Her story is a reminder of how deeply intertwined privilege, identity, and morality were during one of the most tumultuous periods in American history.