Last updated: April 24, 2025

Article

Stargazing Through History: The Astronomical World of Martin Van Buren’s Era

Public Domain

Celestial Catalogs and Cosmic Clues

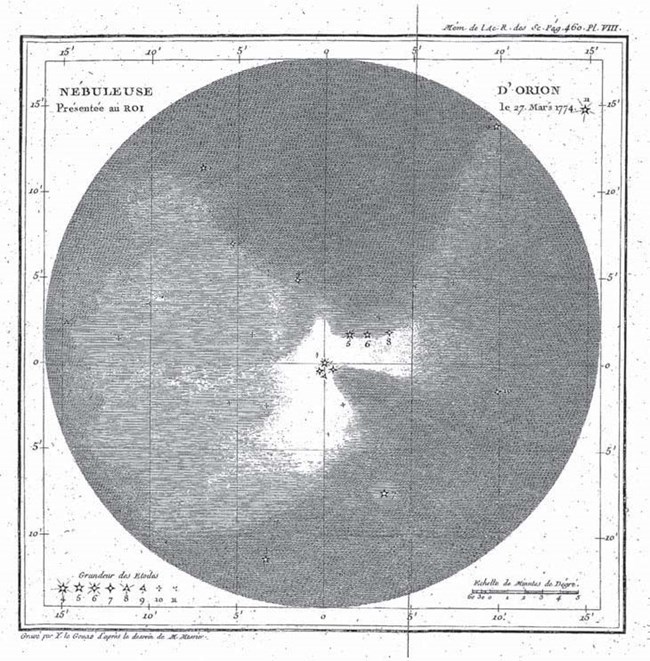

The groundwork for modern stargazing was laid in 1781 by Charles Messier, who completed a catalog of 103 star clusters and nebulous objects. Originally intended to help comet hunters avoid false alarms, the Messier Catalogue soon became a reference guide for astronomers around the world—and remains one today.

As the new century dawned, William Herschel made another leap. In 1800, he discovered infrared radiation while experimenting with sunlight and thermometers, proving that invisible light existed beyond the red end of the spectrum. His work helped launch the field of spectroscopy, which allows scientists to decode the chemical makeup of stars.

Just a year later, in 1801, Italian astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered Ceres, the largest object in the asteroid belt. Though first thought to be a new planet, Ceres was later classified by Herschel as a different kind of object altogether—an “asteroid.” Today, it’s recognized as a dwarf planet.

By 1814, German optician Joseph von Fraunhofer had developed a precision spectrometer and noticed hundreds of dark lines cutting across the solar spectrum. These “Fraunhofer lines” would later reveal the elements found in the Sun, giving humanity its first look into the chemistry of stars.

A quarter-century later, in 1838, Friedrich Bessel used the Earth’s movement to calculate the distance to 61 Cygni, a nearby star. This was the first accurate measurement of a star’s distance using stellar parallax—a method that laid the foundation for understanding the scale of the universe.

In 1843, after 17 years of careful observation, Heinrich Schwabe, an amateur German astronomer, announced a repeating cycle of sunspots on the Sun’s surface—an early glimpse into solar activity and internal structure.

And in 1845, Irish astronomer William Parsons built one of the most powerful telescopes of the age. With a 72-inch mirror, it revealed for the first time the spiral structure of galaxies, including the majestic Whirlpool Galaxy (M51), reshaping our understanding of the universe’s vast architecture.

Public Domain

Capturing the Skies

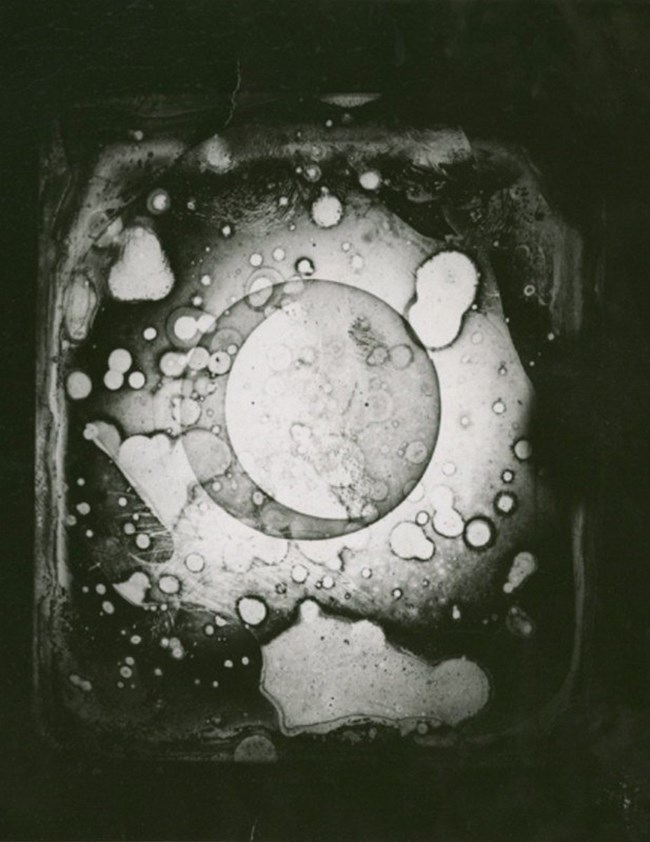

The mid-19th century also saw photography enter the field of astronomy. In 1839, French inventor Louis Daguerre captured the first photograph of the Moon. In 1840, New York University professor John William Draper refined the method and immortalized the Moon’s crescent form with a daguerreotype—launching the era of astrophotography. Just five years later, French scientists Jean Foucault and Armand Fizeau took the first detailed images of the Sun's surface, beginning a new chapter in solar science.

Then came one of the great triumphs of theoretical astronomy. In 1846, German astronomer Johann Galle discovered the planet Neptune—guided not by observation, but by mathematical prediction. French scientist Urbain Le Verrier had charted its location based on gravitational anomalies in Uranus’s orbit, demonstrating the power of celestial mechanics. English mathematician John Couch Adams had reached a similar prediction independently, proving that the universe could be mapped with numbers as well as lenses.

Public Domain

Public Domain

Albany’s Astronomical Ambitions

Just a short distance from Van Buren’s home, the Capital Region was quietly establishing itself as a center of celestial study. In 1856, the Dudley Observatory was founded in Albany—New York’s answer to Europe’s great scientific institutions. Thanks to a generous endowment from philanthropist Blandina Dudley, the observatory soon offered public telescope viewings, cutting-edge star catalogs, and national timekeeping services. Albany had become a beacon for astronomical discovery.

Though the grand university plans that accompanied it never fully materialized, Dudley Observatory made an outsized impact in its own right—bringing the stars a little closer to the people of New York and contributing to the ever-growing map of the heavens.

Public Domain

From Kinderhook to the Cosmos

While Martin Van Buren shaped the destiny of a young republic, scientists across continents were reshaping our understanding of the universe. From cataloging distant nebulas to photographing the Moon, measuring the composition of starlight to discovering new worlds through mathematical precision, the period between 1782 and 1862 marked a golden age of celestial exploration. It was a time when humanity, armed with evolving instruments and newfound curiosity, began to lift its gaze skyward—and truly grasp the nature of the cosmos.

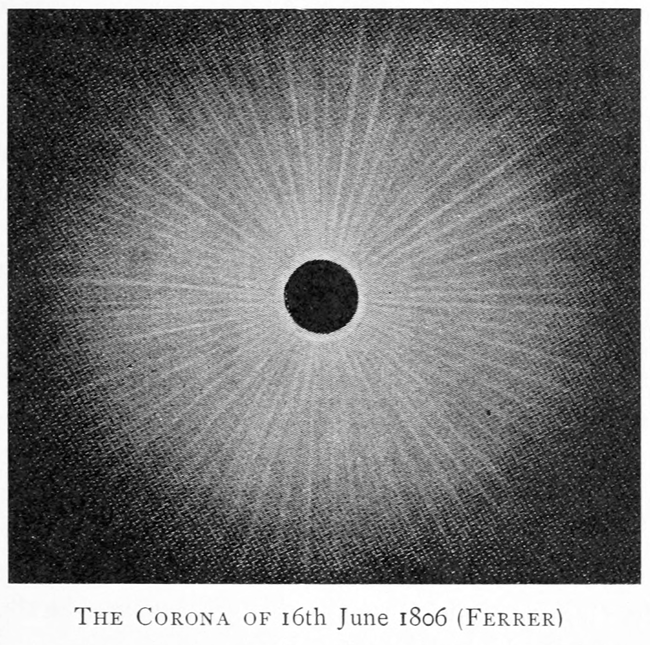

One particularly striking moment occurred in 1806, when a total solar eclipse passed directly over Van Buren’s hometown of Kinderhook, New York. At the time, Martin was 24 years old and living in the village—making it quite possible that he witnessed the eclipse firsthand. Among those who certainly did was Spanish astronomer José Joaquín de Ferrer, who journeyed down the Hudson River from Albany to observe the event from Kinderhook Landing. It was during this observation that Ferrer introduced the term corona to describe the radiant outer atmosphere of the Sun, visible only during totality. His presence, and his contribution to astronomical terminology, forever tied Kinderhook to the scientific legacy of solar observation.

The 1806 eclipse is also famously associated with Tecumseh, the Shawnee leader whose efforts to unite Native American nations challenged U.S. expansion in the early 19th century. According to historical accounts, Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa—the Prophet—used foreknowledge of the eclipse to inspire followers and lend supernatural weight to their movement. The eclipse thus became a moment where celestial phenomena intersected with earthly politics, belief systems, and resistance.

It is remarkable that three individuals—Martin Van Buren, José Joaquín de Ferrer, and Tecumseh—each experienced this rare eclipse from their unique vantage points. Though their lives followed vastly different paths, they were momentarily united beneath the shadow of the Moon, under the same darkened sky that continues to inspire wonder to this day.