INTRODUCTION

By Marian Albright Schenk

FOREWORD

By Dean Knudsen

SECTION 1

Primary Themes of Jackson's Art

SECTION 2

Paintings of the Oregon Trail

SECTION 3

Historic Scenes From the West

|

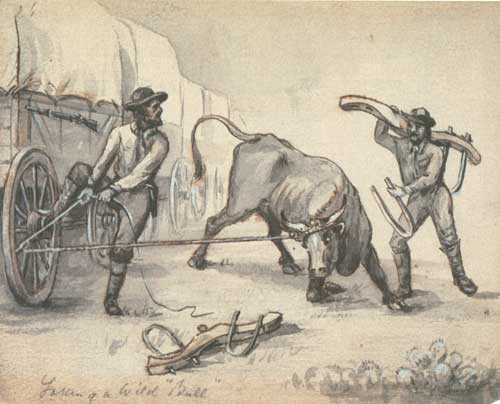

| In what is almost certainly a self-portrait, Jackson shows how a bullwhip was used to keep several teams of oxen in line. As he wrote in his autobiography, "Only the voice of a master can make twelve bulls gee or haw with a single word. Only a cunning hand can make an 18-foot whip crack out like a rifle shot. . ." (SCBL 281) |

Section 2: Paintings of the Oregon Trail

THE FINE ART OF BULLWACKING

By the time William Henry Jackson first stepped onto the Nebraska plains in 1866 he had already worked in a photographic studio and served as a soldier in the Civil War. However, nothing had prepared Jackson for the back-breaking labor he would endure during his brief stint as a bullwhacker.

Jackson and his companions must have presented an amusing sight to the hard-bitten wagonmaster who hired them to work with his freight wagons. These young men in their city clothes undoubtedly had to endure the ridicule and taunts of the more experienced westerners. Added to this was the fact that Jackson had never worked with draft animals before and had to learn his new job from scratch.

Jackson's indoctrination as a bullwhacker began early on a June morning in 1866. As he later described the experience:

My practical education began at dawn on Wednesday morning with the booming cry "Roll out! Roll out! The bulls are coming!!" In an instant the whole camp was alive with swollen-eyed men stumbling over each other. . . At once the work of yoking up began, and any greenhorn observer would have noted nothing more than a score and a half of men in indiscriminate pursuit of enough steers to pull his own wagon.

But even though most of us were utterly inexperienced, we had already been told how exact the process was: Each driver had his own twelve bulls to identify, beginning with the "wheelers," then the "pointers," the "swing cattle" (three yokes) and the "leaders," six pairs in all, each of which had to be yoked and bowed and chained in proper position.1

|

| As a young man, William Henry Jackson appears to have liked the idea of posing while reading a newspaper. Perhaps he felt the informality helped him appear relaxed, while at the same time looking mature. (SCBL 2004) |

The combination of unbroken oxen and inexperienced teamsters must have been frustrating for even the most patient wagonmaster. Jackson himself sheepishly admitted that it took him eight hours to complete the task of yoking and hitching his oxen the first day on the trail. Such an effort left him and his companions completely exhausted.

Needless to say, this performance cut down on the distances the wagons were able to cover. Allowances were made so that during the first week, the greenhorns only had to make one drive of about ten miles each day. Later, as Jackson became more accomplished at handling his oxen, he was able to get his animals yoked and ready in less than an hour.

With practice and repetition the work eventually became routine, and the bullwhackers were able to make two drives during the day for a total of fifteen miles. The day began at 4 A.M., and the wagons were kept on the road until about 10 A.M. At that time the men could halt and eat their breakfast while the oxen were allowed to graze. After frying some salt pork and boiling coffee, the freighters greased the hubs of their wagons, and around 2 P.M. the bulls were again yoked and hitched to the wagons so the westward journey could resume until sunset.

This grinding routine repeated itself each day on the trail, and was only interrupted by mechanical breakdowns or severe weather which made travel impossible. Desertions among the bullwhackers were common, as working conditions were rugged and the food poor. Despite the isolation, other passing trains offered ready employment.

1. Jackson, Time Exposure, 111-112.

|

| Yoking a Wild Bull. Unsigned and undated. 11.0 x 14.1 cm. (SCBL 48) |

|

scbl/knudsen/sec2c.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-2006 |

|