Last updated: September 30, 2025

Person

Ralph Lane

National Park Service

Best remembered for his role as Governor of the 1585-1586 Military Colony, Ralph Lane wore many hats during his lifetime. He was a soldier, sheriff, member of parliament, and sailor. Lane’s skills and abilities made him an ideal candidate to help command a privateering base, but not to lead diplomatic relations with local Algonquian-speaking tribes. Due to circumstances outside of his control, Lane became the face of English military power to the Roanoke tribe and led the first major attack on the Natives by the English.

Ralph Lane was born around 1532 to parents Sir Ralph Lane and Maude Parr (a cousin of Catherine Parr, the last wife of Henry VIII). He first appears in the historical record in 1558 after being elected to the newly created Higham Ferrers parliament seat. At the time, his older brother Robert was already a member of parliament, which may have contributed to Ralph getting his seat. Lane, being young and relatively untried, did not seem like an obvious choice, but won reelection to the seat in 1563. By 1568, he served as equerry (officer of honor) for Queen Elizabeth I's stable, introducing him to the complex world at the Queen's Court.

In 1571, Lane received a promotion to Commissioner of Piracy. Besides his work in the Queen's stable, Lane was an asset in military campaigns. He became a captain in the Netherlands in 1572-73 and became heavily involved in other maritime affairs. In 1583, Lane went to Ireland to supervise and direct the construction of forts. He returned to England in 1585 to lead Sir Walter Raleigh's proposed colony in the New World.Sir Walter Raleigh aspired to set up a privateering base and create an English stronghold in the New World. Raleigh planned to send 600 sailors and soldiers, split between seven ships. The sailors, who made up the majority of the men, would be under the command of Sir Richard Grenville. Once they arrived on Roanoke Island, the soldiers would be under the command of Lane.

The ships departed from Plymouth in April with Lane and Grenville aboard the flagship, the Tyger. Also aboard the Tyger were the artist John White, the scientist Thomas Hariot, and the Algonquian translators, Wanchese and Manteo. The fleet encountered trouble almost immediately with a storm in the Atlantic separating them. Several of the ships became badly damaged, with one ship destroyed. The Tyger arrived first in the West Indies, anchoring at St. John. When they arrived, Lane went ashore with 120 men to build a fortification to protect the men from the Spanish. The Tyger would be repaired, and they would wait for the rest of the fleet. The Spanish sent a small band of men to investigate, but no fighting took place. Another ship, the Elizabeth, arrived, and the two sailed for Roanoke Island. Along the way, Grenville engaged in privateering, attacking and stealing a ship from the Spanish. Lane grew angry by the further delays. He wanted the colony to have ample time to prepare for winter, and the delays lost them precious time.

When they reached the island of Wococon (Ocracoke) at the end of June, a storm made it difficult to access the inlet. The Tyger's pilot, Simon Fernandes, attempted to steer the ship into the inlet, but instead ran the ship aground. Because Grenville had insisted on most of the supplies being aboard the Tyger, saltwater ruined most of the supplies. While other members of the voyage blamed Fernandes for the loss of supplies, Lane did not. After salvaging what they could, Lane led the men exploring along the Pamlico Sound while the Tyger was repaired. Their first stop was to pick up the 30 or so men left by Captain Reymond of the Red Lyon. They also stopped at several Algonquian villages along the way. After returning to the Tyger, the men sailed north to Roanoke Island.

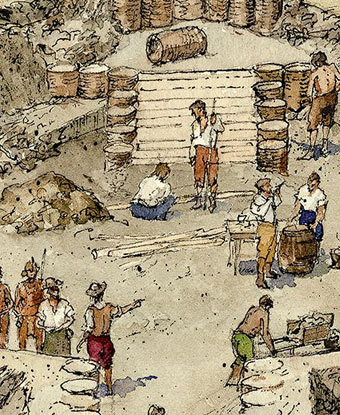

Upon arrival on Roanoke Island, Ralph Lane began directing the construction of an earthen fort. A scientific workshop was constructed for Joachim Gans and Thomas Hariot to work in, homes, and a jail. Grenville departed in August, leaving Lane with 110 men, limited supplies, and a promise to return the following year. Wanchese, one of the translators, returned to the Roanoke tribe sometime in August, leaving Manteo as the only translator. The colony relied heavily on the Roanoke tribe for food and other supplies. Wingina, chief of the Roanoke people, had welcomed the English back, but quickly learned that the English needs overwhelmed the Roanoke people’s supplies. Lane led small exploration groups all over the area, creating a record of the area and those who lived there. A drought affected the area, and as fall moved into winter, food became even more scarce than usual. Members of the Roanoke tribe died due to English diseases. Tensions grew between the Roanoke tribe and the English colony, planting seeds of mistrust.

In the spring, the Roanoke tribe moved to the mainland. Ensenore, a father figure to Wingina, and Granganimeo, his brother, died of disease. These deaths caused Wingina to change his name to Pemisapan. Pemisapan told the English that other tribes in the area had a plan to attack them. The English, led by Lane, captured Skiko, the son of Menatonan, chief of another local tribe, the Chowanoke. Menatonan revealed that Pemisapan and the other Roanoke people were plotting to attack the English, not the Chowanoke. Ralph Lane, a man of action rather than words, did not try to confirm the claims and declared Pemisapan his enemy. The Chowanoke and Roanoke were enemies, and both groups could have tried to use the English to defeat their enemy. It’s possible that the Chowanoke or the Roanoke really were trying to kill the English. Whatever the reason, Lane used the claims as justification to attack the Roanoke at Dasemunkepeuc. It was a surprise attack, with Pemisapan injured very quickly. When he tried to escape, an Irishman named Edward Nugent chased him down and beheaded Pemisapan.

The English had made enemies of the Roanoke tribe. The supplies were dwindling, and they needed help fast. Grenville had not yet returned, and the men were struggling without his help. Lane needed to act quickly if they were to survive. Luckily for them, Sir Francis Drake anchored just off the coast of the outer islands and came to Roanoke for freshwater. After hearing what happened, Drake volunteered to help the men. Lane wanted to complete their mission and asked for a smaller boat. Before they could continue, a storm blew in and ended any opportunity for further exploration. Lane was left with little choice as the colonists quickly packed up and departed. Several chests of notes by Lane and Hariot were thrown overboard and lost in the haste to depart. Other than the initial storm, the return trip to England was relatively quiet. In the excitement over Drake’s triumphant return, Lane’s failure at Roanoke was overlooked. Lane, who had initially been very supportive of the colonization attempt on Roanoke Island, came back a changed man. While he was not against a colony, he did not see it as the land of opportunity that people claimed it to be. In his report to Raleigh, Lane discussed the difficulties of the area, and the lack of resources needed to make Raleigh rich. When Hariot published his report, Lane provided the foreword, expressing his agreement with Hariot’s conclusions.

There is limited information about Lane’s life after the military colony. He became involved in defending England from the Spanish Armada in 1587-88 in Norfolk and then embarked on an expedition to Portugal in 1589 and again in 1590. Lane received an appointment as muster-master general of Ireland in 1591-92 and received a knighthood in 1593. He was heavily involved in the Nine Years’ War, receiving an injury in 1594 that affected him for the rest of his life. Also in 1594, Lane became Keeper of Southsea Castle at Portsmouth, a role that would eventually go to his nephew Robert Lane. Lane used a deputy to fulfill his role as he resided in Dublin. He held the position of muster-master until his death in 1603. Lane died due to complications of his 1594 injury and was buried on October 28th in St. Patrick’s Church in Dublin, Ireland.

As he wasn’t a part of the Lost Colony group, Ralph Lane’s role in English colonization is often overlooked. He was at the center of the first major English conflicts with native tribes, setting the stage for further struggles on Roanoke Island. Lane’s use of force and his soldier mindset set the stage for the fallout with the Roanoke people. History paints him at worst a villain, at best a man poorly suited for setting up diplomatic relationships with Native people. Whatever the answer, Ralph Lane’s tenure as governor is an integral piece in the Lost Colony story.