Last updated: January 6, 2025

Place

Lewis’s Departure from Pittsburgh

Senator John Heinz History Center

Benches/Seating, Food/Drink - Snacks, Gifts/Souvenirs/Books, Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Picnic Table, Restroom, Restroom - Accessible, Scenic View/Photo Spot, Trailhead, Trash/Litter Receptacles, Water - Drinking/Potable, Wheelchair Accessible

Lewis and Clark NHT Visitor Centers and Museums

This map shows a range of features associated with the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, which commemorates the 1803-1806 Lewis and Clark Expedition. The trail spans a large portion of the North American continent, from the Ohio River in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, to the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon. The trail is comprised of the historic route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, an auto tour route, high potential historic sites (shown in black), visitor centers (shown in orange), and pivotal places (shown in green). These features can be selected on the map to reveal additional information. Also shown is a base map displaying state boundaries, cities, rivers, and highways. The map conveys how a significant area of the North American continent was traversed by the Lewis and Clark Expedition and indicates the many places where visitors can learn about their journey and experience the landscape through which they traveled.

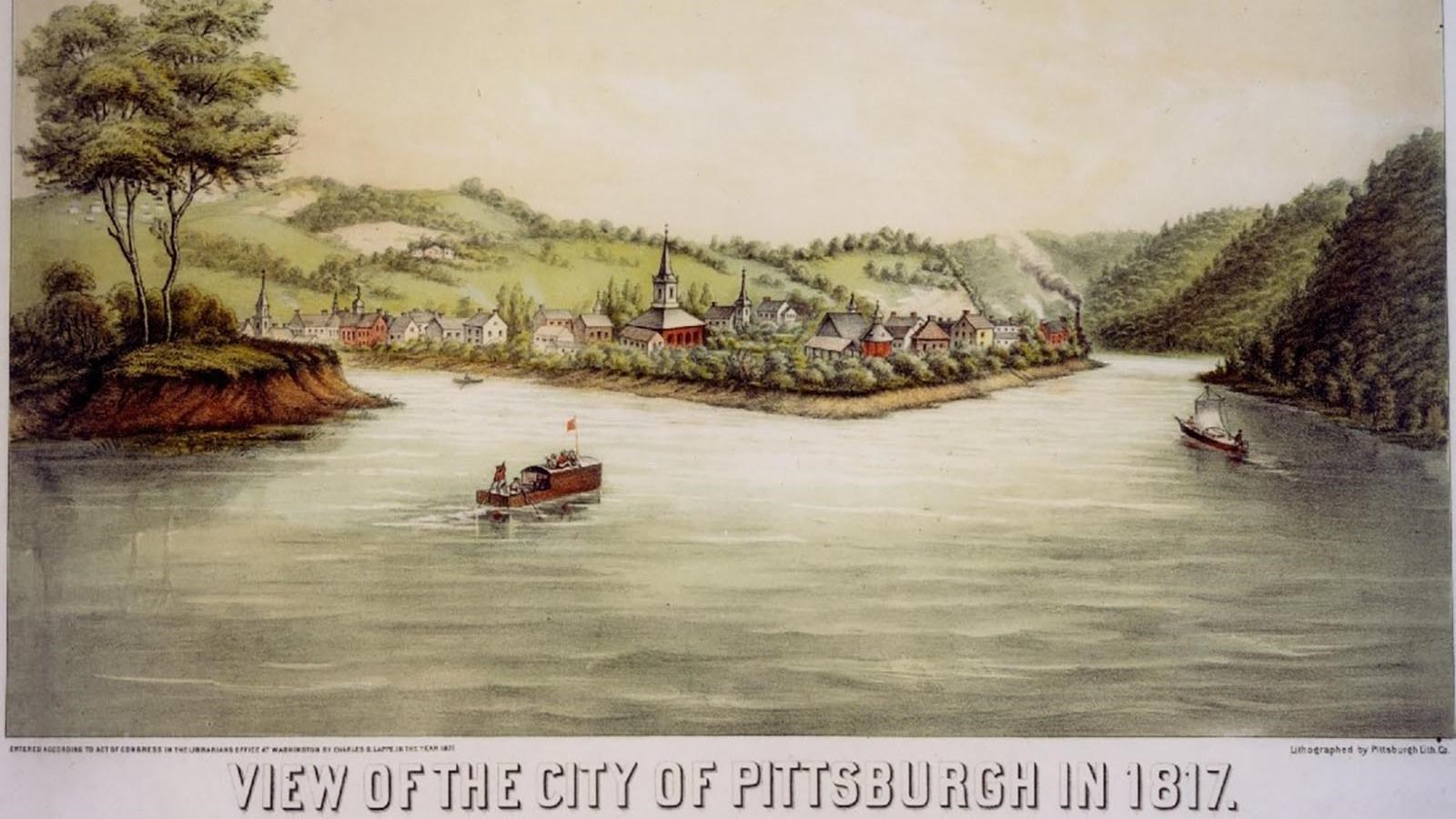

The point where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet to form the Ohio River has been a meeting point and site of commerce and conflict for thousands of years. Delaware, Shawnee, Haudenosaunee, and many other people frequently took boats from here to the Mississippi River, or even all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

By 1800, Pittsburgh was populated by European-American settlers and was known for its boat-building industry.

Meriwether Lewis was familiar with this place: he had been stationed here two years earlier at Fort Fayette, an American fort that served as a supply depot for other forts on the Ohio. Lewis ordered goods for the expedition to be shipped here.

Lewis needed a boat that could take him upstream—he knew they’d be navigating the Missouri River against the current.

Canoes, dugout boats, and bateaux (flat-bottomed, lightweight riverboats) had long been used to transport materials up or down the river, but they had limited cargo capacity. Keelboats—in heavy use by the 1790s—could transport forty to fifty tons of material upriver quickly due to their long, narrow shape, heavy wooden keel, and pointed prow. Men used iron-tipped poles to push against the river bottom and cajole the boat upstream.

When Lewis arrived at Fort Fayette on the afternoon of July 15, 1803, he saw only the skeleton of the fifty-five-foot keelboat that was supposed to be ready for him. And the boat builder was drunk.

Lewis waited six weeks for the boat to be ready. While he waited, Lewis prepared for the journey. He recruited new crew members.

He waited to hear back from William Clark, whom he asked to join him as co-commander of the expedition.

He also worried. The water level dropped as the summer wore on. Would there be enough clearance or current for the boat to move easily down river?

He paid a river pilot, T. Moore, to get the boat and crew to the Falls of the Ohio River.

As soon as the boat was ready—August 30, 1803—they hopped on board and set off.

About this article: This article is part of a series called “Pivotal Places: Stories from the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.”