NPS image.

Introduction

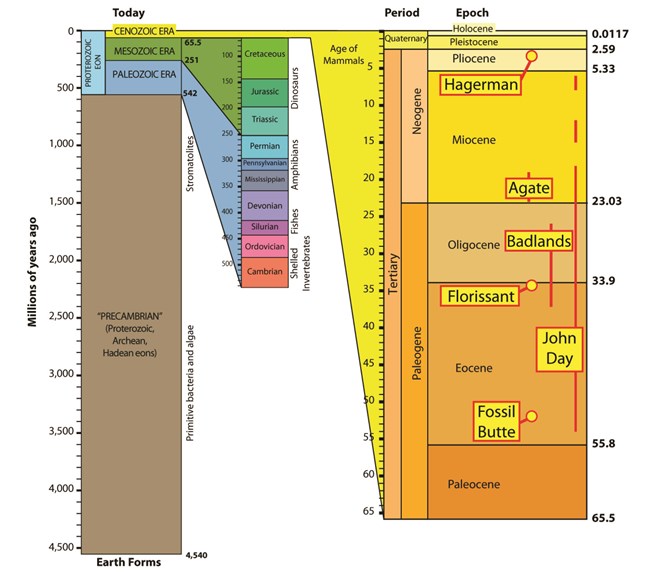

Life began on Earth early in the planet’s history, certainly by about 3.7 billion years ago and perhaps more than 4 billion years ago. The oldest known fossils that are widely supported are of microbes and microbial structures such as stromatolites. Other important milestones in the early part of the history of life include the origination of eukaryotes (complex single-celled organisms), multicellular organisms, and the accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere. Very ancient fossils are difficult to recognize because they are often small, rare, and look like other things, so in general our knowledge of early milestones in life is hazy. The National Park System contains little record of these early events because rocks of the right age and composition are uncommon in parks.

However, national parks do contain a remarkable record of life throughout the Phanerozoic Eon (Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic Eras) and contain diverse fossils that provide information on the major milestones in the evolution and diversification of life. There have been four major diversification events in the Phanerozoic that have profoundly impacted evolution and the diversity of living organisms on Earth. These events are:

-

Cambrian Explosion

-

Life on Land

-

Angiosperm (Flowing Plants) Terrestrial Revolution

-

Cenozoic Climate Change

Cambrian Explosion

NPS photo by Justin Tweet.

The Cambrian explosion was a time of rapid diversification of life when most of the major groups of animals first appeared over a time span of about 40 million years. It started at the beginning of the Cambrian Period, 538.8 million years ago. The Cambrian explosion is particularly important in the history of life because it was the first radiation of life with hard parts when many groups of animal life originated or became established, including arthropods, echinoderms, mollusks, and vertebrates. Some of these groups would dominate the Cambrian, such as trilobites (the first abundant arthropods), and others would become dominant later on.

The National Park System has a limited fossil record for the early Cambrian. A few parks, like Death Valley National Park and Mojave National Preserve, both in California, have a continuous rock record from the Precambrian through to the Cambrian. However, with the exception of trace fossils such as Skolithos burrows, these rocks are not fossiliferous.

UCMP photo by Dave Strauss.

During the Cambrian, animal life experimented with many body plans. Some of these experiments flourished briefly but did not last. For example, radiodonts, an early type of arthropod, were dominant predators in the Cambrian but did not survive past the Devonian. Radiodont fossils have been found at Mojave National Preserve. The first reef-building animals were a group of sponges (archaeocyathids) that evolved, spread across the world, and went extinct, all within the Cambrian. Some of their fossils have been found in parks in Alaska, including Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve.

Related Link

Photo by Linda S. Lassiter.

Other Cambrian fossils of extinct groups in units of the National Park System include bradoriids, eocrinoids, and hyoliths from Grand Canyon National Park and Grand Canyon-Parashant National Monument in Arizona. Bradoriids were a type of early crustacean-like arthropods that went extinct at the end of the Cambrian. Eocrinoids were early echinoderms that went extinct at the end of the Silurian. Hyoliths were small animals with conical shells that reached their peak during the Cambrian but persisted until the end of the Permian.

Life on Land

NPS Photo by Tom Paradis.

Life on land dates back to the Precambrian in the form of microbes, but it wasn’t until the Devonian when plants fully colonized dry land and landscapes became forested and green. Terrestrial arthropods such as millipedes and insects radiated in this new landscape, and amphibious vertebrates began to emerge.

The first terrestrial plants, dating to the Middle Ordovician, were likely very small and similar to algae, and had not yet developed roots, woody tissues, leaves, or seeds. With each of these developments, plants acquired features that allowed them to grow larger. The first vascular plants probably date to the Late Ordovician. The Devonian saw many new groups of plants first appear and the first forests. Early forests contained spore-bearing trees that were primitive relatives of ferns.

Devonian plant fossils in the National Park System are present in Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park in Washington DC, Maryland, and West Virginia, Upper Delaware Scenic and Recreational River in New York and Pennsylvania, and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve in Alaska.

National Science Foundation. (Note: Tiktaalik fossils have not been found in national parks.)

The Devonian is also known as the time period when vertebrates began to colonize land. Fossils of the earliest land vertebrates have not yet been found in National Park System areas, but fossils of a Devonian aquatic cousin, a lobe-fin fish, are found in Grand Canyon National Park. In general, the Devonian is also known as the Age of Fishes for the great abundance and diversity of fishes that lived at the time, including jawless fishes, armored fishes, cartilaginous fishes, lobe-finned fishes, and ray-finned fishes. Death Valley National Park in California and Grand Canyon National Park in Arizona both have notable Devonian fish fossils, which usually consist of bony plates and/or teeth.

Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution

NPS photo by Geoscientist-in-the-Parks G. William M. Harrison.

Photo by E.A. Wheeler, NC State University.

Flower-based reproduction gives angiosperms a competitive advantage over other groups of plants. Instead of relying on wind or water to spread pollen or spores to other plants for reproduction, angiosperms attract animals (especially insects) to their pollen-bearing flowers with colors, scents, and other lures. The animals in turn spread pollen directly to other flowers. The fruits evolved by flowering plants are also part of their reproductive strategy: animals that take the fruits end up dispersing the seeds they contain to new places. The spread and radiation of flowering plants also spawned evolutionary bursts in insects and herbivores, including mammals. Many pollinators and plants became closely specialized to each other. Fruits and flowers became important food sources for a wide variety of invertebrates and vertebrates.

Related Link

NPS photo by Austin Shaffer.

The National Park System has a significant fossil record of Cretaceous plants. The Cretaceous flora in Big Bend National Park in Texas contains both conifers and angiosperms and includes such subtropical plants as laurels, mangroves, and palms. Cretaceous leaf impressions and petrified wood are known from Colorado National Monument in Colorado and Mesa Verde National Park in Colorado. In Denali National Park in Alaska, researchers have observed at least several different species of angiosperm leaves.

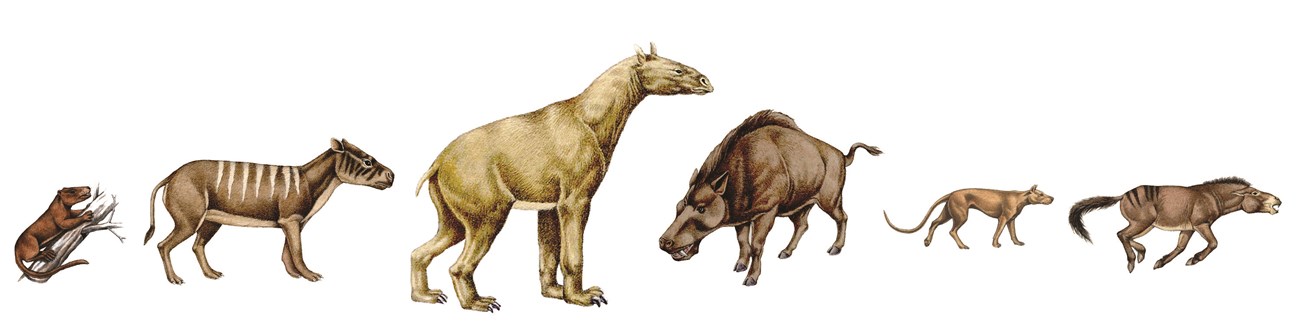

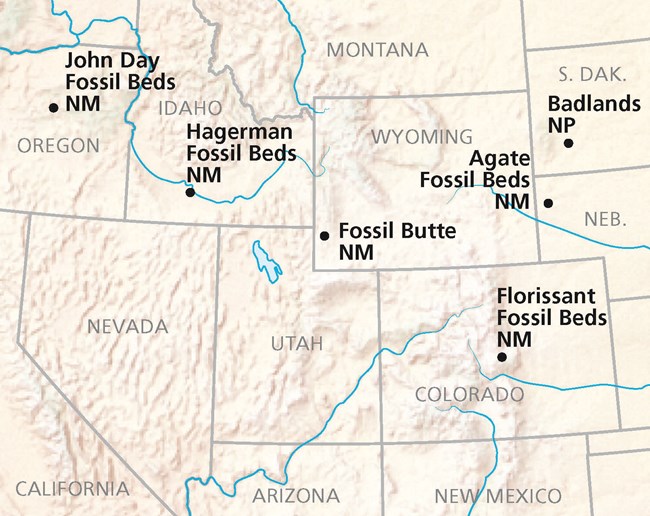

Mammal Evolution in the Cenozoic Era

The Cenozoic Era in North America has been marked by pronounced changes in the climate, and mammal evolution during this time interval is closely tied to these climatic changes. During the last 66 million years, both the average temperatures and the amount of precipitation varied greatly. The National Park System contains a number of fossil parks that, especially when viewed together, provide a remarkable record of evolution during the Cenozoic.

Parks with an important Cenozoic fossil record for mammals include:

-

Agate Fossils Beds National Monument, Nebraska [Mammal Fossils] [AGFO Geodiversity Atlas] [AGFO Park Home] [AGFO npshistory.com]

-

Badlands National Park, South Dakota [Geology & Paleontology] [BADL Geodiversity Atlas] [BADL Park Home] [BADL npshistory.com]

-

Big Bend National Park, Texas [Fossils in Big Bend National Park] [BIBE Geodiversity Atlas] [BIBE Park Home] [BIBE npshistory.com]

-

Florissant Fossil Beds National Monument, Colorado [Paleontology Program] [FLFO Geodiversity Atlas] [FLFO Park Home] [FLFO npshistory.com]

-

Fossil Butte National Monument, Wyoming [Fossils & Geology] [FOBU Geodiversity Atlas] [FOBU Park Home] [FOBU npshistory.com]

-

Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument, Idaho [HAFO Fossils] [HAFO Geodiversity Atlas] [HAFO Park Home] [HAFO npshistory.com]

-

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon [JODA Fossils] [JODA Geodiversity Atlas] [JODA Park Home] [JODA Npshistory.com]

-

Niobrara National Scenic River, Nebraska [NIOB Fossils] [NIOB Geodiversity Atlas] [NIOB Park Home] [NIOB npshistory.com]

Badlands National Park in southwestern South Dakota has one of the best known Cenozoic fossil records in the world. Fossiliferous rocks of Late Eocene and Oligocene age (Paleogene) span the age of a major climatic shift in North America from warm and humid conditions to cool and dry conditions. Oligocene fossils from Badlands include titanotheres, camels, and early horses. Oligocene fossils include entelodonts recovered from the “Big Pig Dig,” nimravids (false saber-toothed cats), and Santuccimeryx, a new genus of tiny hornless deer.

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument in central Oregon has a rock record that spans much of the Cenozoic. The Eocene Epoch of the Paleogene Period experienced the warmest temperatures and precipitation levels of the Cenozoic Era. The John Day Basin was hot, wet, and semitropical during the Eocene and contained diverse forests that were inhabited by a variety of large mammals including brontotheres, “marsh rhinos,” primitive horses, and carnivores.

Conditions were cooler and drier by the Miocene Epoch of the Neogene Period. The John Day Basin had more open habitats as well as wooded areas, and grasslands were starting to appear. Burrowing beavers, and running-adapted herbivores like camels and early horses lived in the open areas.

Graphic by Jason Kenworthy.

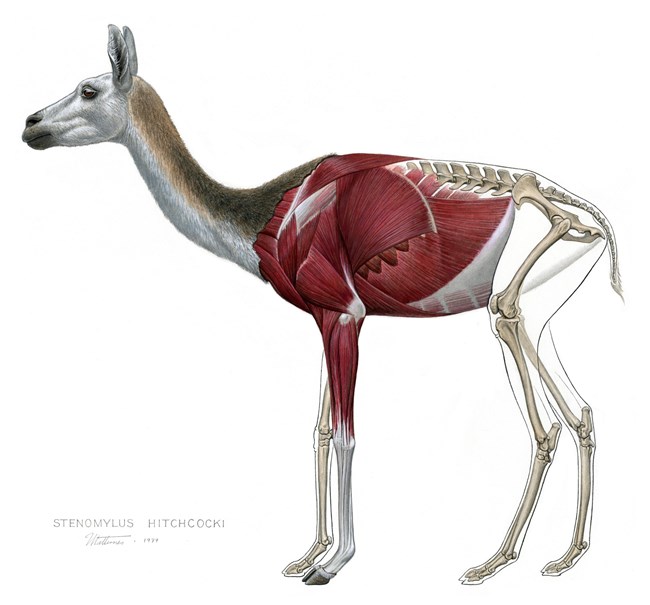

The climate in Nebraska where Agate Fossil Beds National Monument and Niobrara National Scenic River are located was also getting drier in the Miocene when grasslands were starting to become dominant. Fossils of the small rhino Menoceras, the small gazelle-camel Stenomylus, and the large burrowing beaver Paleocastor have been recovered from Agate Fossil Beds.

Climate variations in the Pliocene Epoch impacted the fauna of Hagerman Fossil Beds National Monument in Idaho. More than 200 species of fossil plants and animals have been recovered from the Glenns Ferry Formation in the monument from sediments that were deposited in wetland, riparian, lacustrine, and grassland savanna environments. During the interval when the Glenns Ferry Formation was being deposited, the climate experienced a rapid cooling event followed by rapid warming.

Image (right): Large mammals like the “marsh rhino” (Zaisanamynodon protheroi) lived in central Oregon, 40 million years ago during the Eocene. These large semi-aquatic herbivores inhabited rivers and other bodies of water within the semitropical forest.

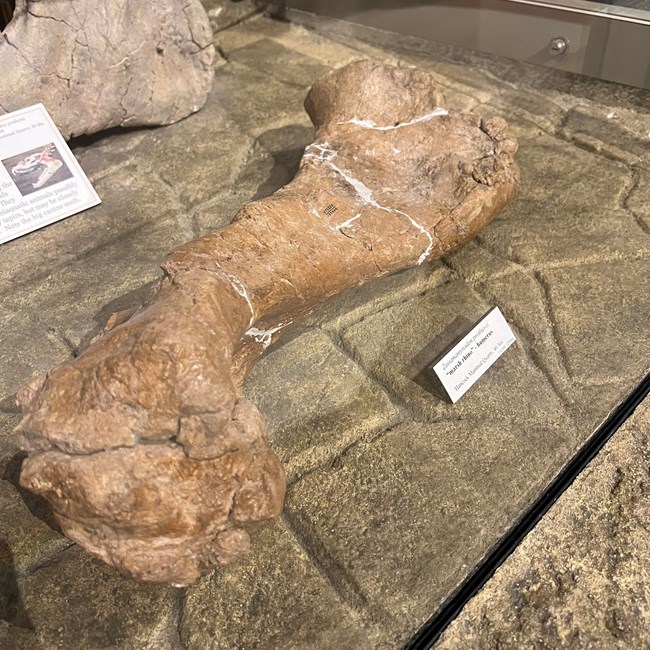

NPS photo.

Image (right): Santuccimeryx elissae, a tiny Oligocene deer recently described from Badlands National Park, weighed between 3 and 5 pounds.

Illustration by Benji Paysnoe

Image (right): Anatomical illustration showing the outer form, musculature, and skeleton of small gazelle-camel Stenomylus, Agate Fossil Beds National Monument.

Illustration by Jay Matternes. Harpers Ferry Center Commissioned Art Collection.

Artwork by Jay Matternes, courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution.

Last updated: February 28, 2025