INTRODUCTION

By Marian Albright Schenk

FOREWORD

By Dean Knudsen

SECTION 1

Primary Themes of Jackson's Art

SECTION 2

Paintings of the Oregon Trail

SECTION 3

Historic Scenes From the West

|

| William Henry Jackson provided his own caption on the back of this photograph. It reads, "Sept. 30, 1921. WHJ in Mancos Canyon—under the X at the top of the mesa is located the 2 story cliff house discovered and photographed by him in 1874." (SCBL 1048) |

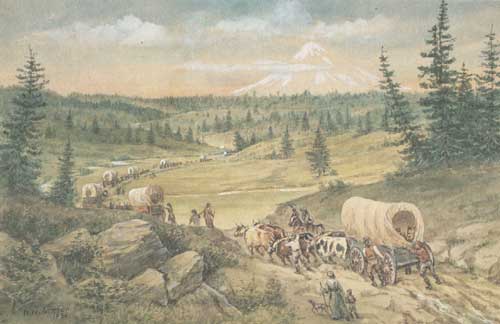

Section 2: Paintings of the Oregon Trail

NEARING THE JOURNEY'S END

Two hundred miles west of Three Island Crossing, emigrants on the Oregon Trail caught their first glimpse of the Blue Mountains. These mountains formed a natural barrier along the eastern border of the Oregon Territory, and emigrants had to be sure to make their way through them before the first heavy snowfall, or risk the fate suffered by the Donner Party in the Sierra Nevada mountains in California.

After walking halfway across a continent, and making hundreds of decisions about such things as what type of wagon they should use, when to leave, how much food to bring along, what tools and furniture will they need, which cut-off to take, and so on—at this point there was only one last major decision to make. Should they pay a toll and continue overland, or should they build a raft and float down the Columbia River?

|

| Completed in 1941, this painting depicts the assembly of early pioneers voting to establish the Oregon Territory. This event took place at Champoeg, along the Willamette River on May 2, 1843—one month before Jackson's birth. (SCBL 47) |

The Barlow Toll Road was established in 1846 by an enterprising businessman named Samuel Barlow. When Barlow first saw the Columbia River in 1845, he did not want to risk rafting. So he and several other people blazed a trail south of the river. Although their efforts nearly cost them their lives due to becoming snowbound, they proved that the new route could work, and the next year Barlow set up the toll road.

While most emigrants complained about having to pay any kind of toll, the improved 30 mile roadway was undoubtedly a welcomed experience after 1,900 miles on the trail. Emigrants had to make the climb up to Barlow Pass, which was the primary route through the Cascade Range. After passing south of Mount Hood the road then made a fairly easy descent into the northern end of the Willamette Valley, south of present-day Portland, Oregon. This toll road was in operation from 1846-1912.

The alternative of floating wagons downriver on rafts was both faster and more dangerous. The river offered an uninterrupted route into the heart of the Oregon Territory, except for the Cascades of the Columbia, where the rafts and their contents had to be hauled several miles around the impassable rapids. The rafts were then reassembled and the perilous journey could be resumed.

An 1847 emigrant named Josiah Beal left this account of his arduous experience on the river:

As soon as the botes were finished, were filled with contents of our wagons and a few wagons were taken to pieces & stowed in the Bote. Stock driven down the Indian Trail. When we got to the cascades we had to unlode our botes and set up our wagons & fill them and make a drive of 5 miles to the lower cascades. The botes were run over the falls and caught below by some Indians that were hired to look after them.1

No one knows for certain how many people made the westward journey on the Oregon Trail. John Unruh, a highly respected scholar of the westward movement has estimated that between 1840 and 1860, 53,062 people emigrated to Oregon, with 1852 as the peak year.2 The problem with these statistics is the inconsistency in which records were kept. The military kept a haphazard count as people passed Fort Laramie, but these are incomplete and sketchy at best, so no irrefutable figures are available.

1. Haines, Historic Sites, 393.

2. Unruh, The Plains Across, 120.

|

| The Barlow Cutoff. Signed and dated 1930. 23.5 x 36.3 cm. (SCBL 46) |

|

scbl/knudsen/sec2v.htm Last Updated: 14-Apr-2006 |

|